The seeds

Wild plant purpose is not to nourish us but to spread their own seeds. How do they do so freely, in an oligopoly?

The notion that ‘yellow’ pasta is of good quality has now been dispelled. The opposite is true.

Our exploration of the wheat supply chain, from seeds to imports and mills, guides us to one of the most renowned ‘Made in Italy’ products: pasta. As highlighted in earlier sections, pasta’s existence hinges on imports since Italy’s durum wheat production falls short of meeting demand.

The majority of industrial pasta factories depend on wheat imports from Canada, Australia, Kazakhstan, and other nations. This imported wheat is then blended with Italian wheat to craft the optimal ‘recipe’ for the pasta industry. Achieving a specific semolina or flour type necessitates seeds with specific genetic traits. A coveted trait within the industrial sphere is a high protein concentration. This parameter is crucial for ensuring the elasticity and durability of dough during industrial processing; seed varieties have been genetically engineered to meet industry requirements. This power dynamic results in the subjugation of agricultural producers to the pasta industry.

The ISMEA report on Agricultural Price Monitoring Systems notes that cultivation contracts are predominantly formed directly between the pasta industry and producers. The industry establishes the purchase price beforehand, considering precise qualitative and technological grain characteristics. In many instances, the industry provides the most suitable seed variety and instructs producers on cultivation techniques to achieve specific characteristics in the final product.

Wild plant purpose is not to nourish us but to spread their own seeds. How do they do so freely, in an oligopoly?

The ancient shared history of wheat and humanity, which began with the domestication of wild cereals by humans, continues today where it all began 11,000 years ago: in Mesopotamia. It may seem like a coincidence, but perhaps it isn’t.

There is nothing similar in Nature, but our flours are increasingly standardized.

To gain a deeper understanding of how an industrial pasta factory operates, we visited the Rummo company. Born in Benevento in 1846 and now in its sixth generation, with around 160 employees and a turnover exceeding 170 million euros (26.5% more than in 2021), Pasta Rummo uses both Italian and imported wheat (from Canada, Australia, and Arizona, among other sources). The company exports to approximately sixty countries, with a focus on France, Switzerland, Spain, the United States, and Canada.

Each day, sixteen trucks arrive at the facility entrance, unloading semolina that is transported directly to the five production lines through an automated system. These production lines run 24/7. Situated near the Sannio river, the facility produces between 3,700 and 4,300 quintals of pasta per day in various formats. Rummo’s pasta factory is among the pioneers in adopting certification for “slow processing” and “cooking resistance.

The certification is granted by Bureau Veritas, a French entity and a world leader in quality certifications—spanning from infrastructure to aerospace, maritime, and oil industries, all the way to industrial facilities and pipelines. Every production batch undergoes laboratory tests and taste evaluations to verify adherence to the certified parameters.

“We select high-quality grains with a high gluten index, containing proteins ranging from 13 to 15, to ensure optimal cooking performance,” explains Mauro Pinto, the plant’s director.

Inside the Rummo pasta factory. Benevento, October 2023. Video by Giuseppe Pellegrino.

Drying is a pivotal stage in pasta production. Italian law n. 570 of 1967 and Regulation 187 of 2001 regulate only specific aspects of the process, such as the use of semolina. For instance, using soft wheat for dry pasta production is prohibited. However, the law doesn’t provide guidance on drying or temperature. In 1880, it took 8-10 days in summer to dry spaghetti; by 1903, with the introduction of mechanical drying, this time reduced to 3-5 days and further to 24-36 hours by 1950 when the drying temperature reached approximately 60°C. Today, machinery operates at very high temperatures, ranging from 90 to 115°C, and short pasta is ready after 2-3 hours. The industrial pasta factory Rummo, certified for “slow processing,” starts at 90°C, gradually decreasing to 80°C and 60°C, taking 5 to 7 hours depending on the recipe. In contrast, other well-known brands operate at high to very high temperatures, from 90°C upwards, reaching peaks of 115°C.

Perché continuiamo a salvare un modello di economia, di produzione e di agricoltura che ci sta distruggendo?

Dalle Mesopotamia al Cilento, biodiversità naturale e umana

Riguardare con uno sguardo innovativo aumentato, che mette insieme anche la possibilità tecnologica

Raising drying temperatures leads to a significant reduction in processing time and cost savings for the industry. Producing a package of pasta in 20 hours instead of 3 makes a notable difference. Furthermore, high temperatures allow satisfactory results even with lower-quality semolina. However, it is evident that pasta dried at 60°C differs from that processed at 115°C. As Roberto La Pira notes in Il Fatto Alimentare, “increasing the temperature during drying allows gluten to form a well-structured network, easily retaining gelatinized starch molecules inside, ensuring the pasta consistently cooks well”. Today, nearly all pastas, including more budget-friendly options, rarely become mushy; modern grains, selected for their high gluten content, are necessary to withstand these drying temperatures. Otherwise, the pasta would break.

Finally, there’s the aspect of color, marketing, and a potentially lower quality of food. When high temperatures are used, the pasta becomes more intensely and darkly colored due to the Maillard reaction. In the case of pasta, it’s a true indicator of the product’s craftsmanship. The law does not regulate terms like “artisanal” or “slow drying”, and companies include them on packaging as they see fit. In this case as well, the industry has managed to turn a flaw into an asset through marketing and advertising, conveying the idea that “yellow” pasta is of high quality. However, the opposite is true: intensely yellow pasta is cooked at very high temperatures, causing damage and depletion to vitamins and proteins. “It is undeniable”, says Giuseppina Tantillo, a professor of Food Inspections at the University of Bari, “that the nutritional quality of pasta is compromised by high drying temperatures because an essential amino acid like lysine is destroyed”.

Inside the Rummo pasta factory: penne enter the drying machine. Benevento, October 2023. Video by Giuseppe Pellegrino.

When considering pasta, supply chains, and power concentration, it’s impossible to ignore the world’s leading company: Barilla G. and R. Fratelli Spa. According to the Global Pasta Market Report and Forecast 2023-2028, the key players in the global pasta market, ranked by magnitude, include Barilla G. and R. Fratelli SpA, Nestle SA, F.lli De Cecco di Filippo Fara San Martino S.p.A., and the Russian JSC Makfa.

In 2022, the global pasta market reached a value of approximately $25.67 billion, with an expected growth of 3.34% between 2023 and 2028, reaching about $31.14 billion. For the Parma-based group, 2022 closed with a turnover of $4.6 billion (+18% compared to the previous year). Like other industrial pasta factories such as Rummo or De Cecco, the pasta industry is flourishing. As Antonio De Cecco, CEO of the eponymous pasta brand, shared with Sole24Ore, 2022 has been exceptionally positive: “We are closing the 2022 balance at $620 million, with a 20% growth in the last year”. Despite the rising cost of grocery carts and 5.6 million Italians facing absolute poverty (9.7% of the population, as highlighted in the Caritas report “Tutto da perdere”), major food industrial groups are increasing profits and opting to relocate their headquarters to low-tax countries. Noteworthy examples include Cargill, headquartered in Delaware (USA), Louis Dreyfus in Rotterdam (Netherlands), and, starting in 2024, Barilla’s safe in the Netherlands will oversee the entire capital of Barilla G. and R. Fratelli Spa, encompassing a significant portion of foreign subsidiaries. Until now, these subsidiaries fell under the London subsidiary, where the group’s digital hub is still based, as reported by Il Corriere della Sera.

Il Made in Italy è solo fumo negli occhi: la chiamano sovranità alimentare ma è conservatorismo malcelato.

As “Made in Italy” increasingly evolves into a brand that facilitates market expansion, capitalizes on globalization, and markets products that are progressively less authentically Italian and local, the multinational Barilla G. and R. Fratelli Spa continues its trajectory of growth and acquisitions. Currently, it operates in over 100 countries, including Russia (which, according to Leave Russia, it has never left). Over time, Barilla has acquired a multitude of brands, such as the Mexican pastas Yemina and Vesta, the Greek brand Misko, the Turkish Filiz, and the Swedish bread brand Wasa. Recent acquisitions include Back to Nature, a U.S.-based brand specializing in healthy snacks under the B&G Foods product holding, and Pasta Evangelists, an English player specializing in fresh pasta and sauces with home delivery, acquired in 2021.

Barilla also controls various brands in different regions, including Catelli, Lancia, Splendor in Canada, and Harry’s in France through Barilla France. However, Barilla’s influence extends beyond pasta. In Italy, alongside the Voiello brand, Barilla oversees groups such as Pan di Stelle, Pavesi, Gran Cereale, and Mulino Bianco.

A 2021 investigation by The Guardian and Food and Water Watch highlighted how a small group of powerful companies controls nearly 80% of the market share for various food products. This control creates an illusion of consumer choice despite the diversity of brands on supermarket shelves and in refrigerators. Transnational corporations wield significant influence across the entire food supply chain, from seeds and fertilizers to slaughterhouses, supermarkets, and various food products, including cereals and beers.

Moreover, numerous studies describe the dry pasta industry as a stable oligopoly.

In addition to this concentration of power along the supply chain, there’s another less-known aspect concerning the corporate structure of Barilla Holding. Eighty-five percent is under the control of the Dutch company Barilla International, managed by the fourth generation of the Barilla family. The remaining 15% has been owned by the Swiss banker Gratian Anda’s company, Gafina, since 1979. Gratian Anda, now the owner of the private bank IHAG, serves as the director and board member of Barilla and holds partnerships in numerous companies, including Pilatus Aircraft and the software company Advonum.

Another significant detail about the multinational pasta company is its expenditure on lobbying activities. As reported by LobbyFacts.eu, in 2022, Barilla spent between 100,000 and 199,000 euros on lobbying activities related to the “Action Plan for the Circular Economy.” These activities focused on proposals empowering consumers for the green transition, revising the packaging and packaging waste directive, implementing the biodiversity protection strategy, and supporting the Green Deal. LobbyFacts also outlines various meetings between members and commissioners of the European Commission and the company’s lobbyists. While these lobbying activities are legal, it’s noteworthy to observe key players and understand how revolving doors operate.

Additionally, Guido Barilla, beyond serving as the director of Barilla Holding Spa, holds the role of an “independent director” at the French multinational Danone SA and sits on the boards of Gazzetta di Parma srl, Gazzetta dell’Emilia, Publiedi srl, Radio Tv Parma Srl, and other companies.

È il caso di Federico Vecchioni, amministratore di BF Spa, che ora ha investito 2 milioni e mezzo per tenere in piedi la testata La Verità.

The lobbying activity of multiglobal companies is not neutral.

In France it took a four-year battle to get NutriScore approved, a traffic light label aimed at helping consumers make healthier food choices when purchasing.

In Italy, the label—meanwhile approved in six other states, including Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Germany, and Switzerland—is unwanted by major companies like Ferrero and industrial associations such as Coldiretti, according to the Great Italian Food Trade website. However, some Italian products with the traffic light label are already being sold on supermarket shelves abroad. Barilla France, for example, has adopted the NutriScore on baked goods sold under the French brand Harry’s, of which it has been the owner since 2009.

In Italy, industrial lobbies and those supporting the “Made in Italy” label seem to outweigh consumer preferences and enjoy government support, as reported in a Le Monde article published on December 26, 2022. The new Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni, has long been opposed to the Nutri-Score. During the last electoral campaign, she described it as an ‘absurd’, ‘discriminatory’, and ‘penalizing’ system for Italian products. Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini dismissed it as ‘nonsense’ invented by ‘multinationals’ or even a ‘secret plot’ orchestrated by Europe against Italy. In Brussels on December 12, 2022, the Italian Minister of Agriculture and Food Sovereignty, Francesco Lollobrigida, who is Meloni’s brother-in-law, portrayed the ‘Nutri-Score model’ as apocalyptic, associating it with ‘synthetic meat’ (not authorized in Europe) and claiming it would cause the ‘desertification of entire territories.’ While opposition to labeling is not new in Italy, what is noteworthy is that it is now backed by the government.

While the Barilla Foundation actively promotes conferences, campaigns, and researches highlighting the threats of the climate crisis to food production, the multinational Barilla continues to financially support media engaged in spreading climate misinformation. One glaring example is the television program “Quarta Repubblica” on Rete 4. Journalist Stefano Feltri, in his newsletter “Appunti,” pointed out, “Watching Quarta Repubblica helps us understand much about how disinformation is carried out. But do Mediaset advertisers, like Barilla and Ferrero, truly condone funding this manipulation of data and science?” He further questions: “Companies supporting media involved in climate misinformation should shoulder the responsibility. For instance, as I stream the show, Barilla’s Voiello pasta, prominently displayed, raises the question – does Barilla genuinely not care that its products are backing climate denial? And does Ferrero, with its Kinder Pinguì, not mind contradicting years of sustainability efforts to be associated with this type of content?”

They market it as sustainability, but it reeks of greenwashing. In recent years, Barilla has worked towards establishing a durum wheat supply chain produced exclusively in Italy to meet local consumer demand. The website states that Barilla is committed to forming supply chain contracts with producers, promoting practices such as crop rotation, soil care, and reduced use of chemical fertilizers. While we may choose to believe in these efforts, the reality is that, to meet the global demand for pasta, Barilla is compelled to import durum and soft wheat, along with other essential raw materials for confectionery products, from countries where monoculture persists, relying on glyphosate and synthetic chemical fertilizers. The truth is that Barilla, much like many other major Italian companies, would struggle to produce a vast quantity of biscuits, pasta, and crackers without importing raw materials from abroad.

We tried to contact Barilla’s press office. They never answered to our interview requests.

We visited Bourgogne in eastern France to meet two producers of soft wheat who supply Barilla-Mulino Bianco. They are members of the Dijon Cereals cooperative, consisting of 3800 farmers who contribute directly to the cooperative. The owners, choosing not to disclose their identity, possess over 1000 hectares of land where they cultivate soft wheat, barley, and sunflowers. They adopted the Mulino Charter in 2021, a set of guidelines for the sustainable cultivation of soft wheat, emphasizing the presence of flowers in the field, crop rotation, and prohibiting the use of glyphosate.

For those supplying Barilla, it is mandatory to sow specific wheat varieties specified by the multinational to ensure that the flour meets the requirements of industrial recipes. One of the owners explains, “In theory, we are not allowed to use glyphosate, but in agriculture, everyone does as they please. It’s a self-declaration. We don’t undergo checks from Barilla or the cooperative, primarily because it would be impractical to monitor everything”

When questioned about whether the products they use have negative impacts on the soil, environment, and health, he admits, “Yes, but this approach allows us to increase production. Neither we nor Barilla are inclined to exclusively produce organically, as it would lead to reduced output, resulting in lower pasta sales and earnings”.

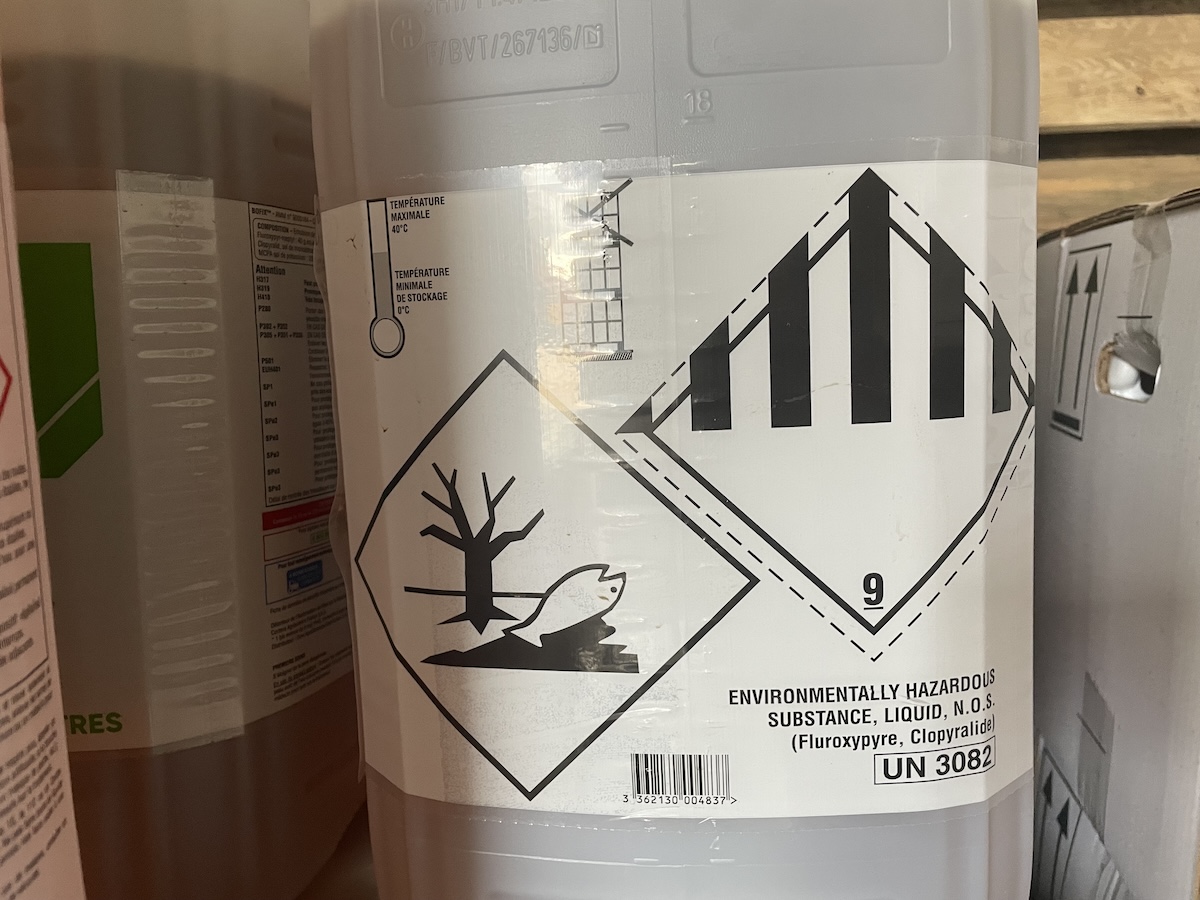

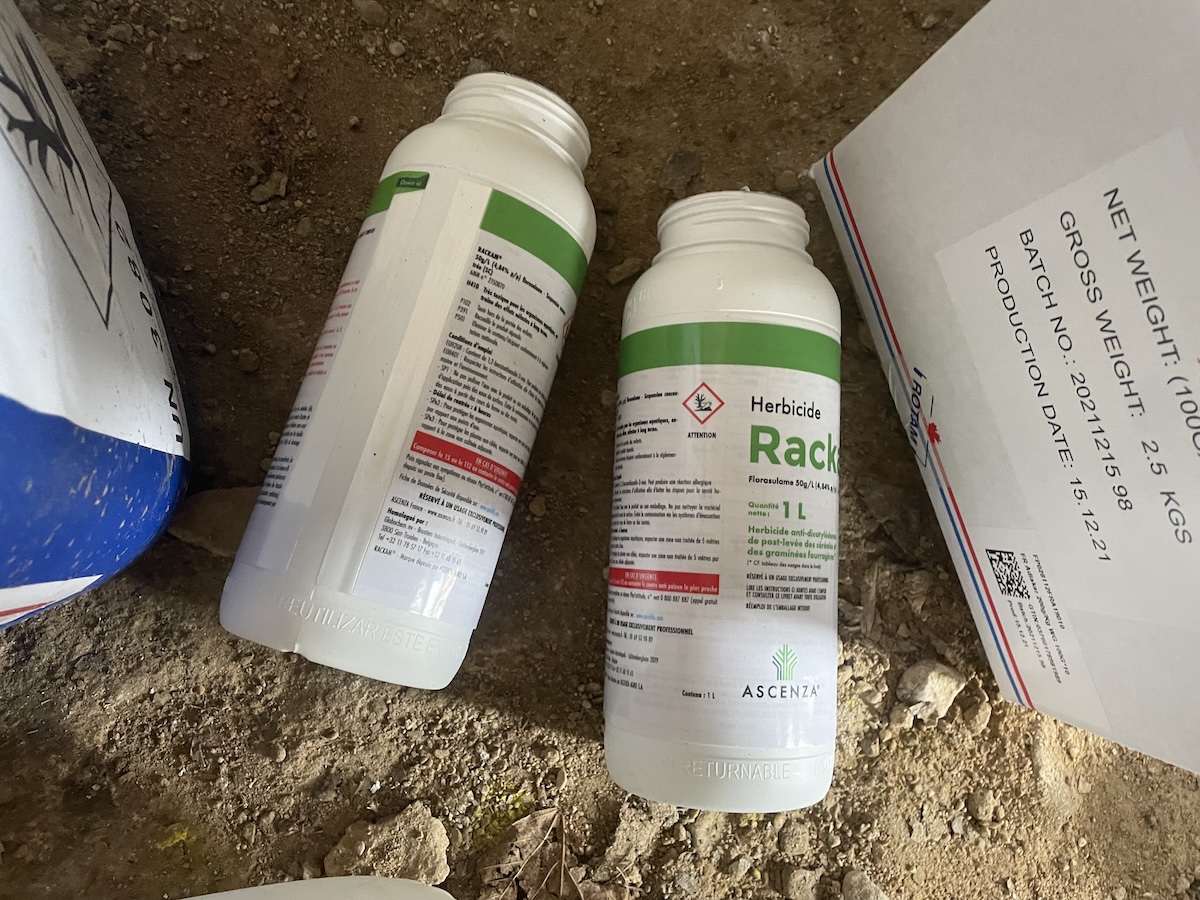

Inside a warehouse of a French agricultural company, in Bourgnogne, in eastern France. The company is part of the Dijon Cereals cooperative together with 3800 farmers who deliver directly to the cooperative, supplier of Barilla-Mulino Bianco. The farm warehouse contains plant protection products, herbicides, and chemical synthesis products used in agriculture. March 2023, photo by Sara Manisera.

This work was conceived and created by Sara Manisera, Bertha Foundation Fellow 2023, with the support of Bertha Foundation, and produced by Slow News.

Video operator: Giuseppe Pellegrino

Illustrations: Vito Manolo Roma