The seeds

Wild plant purpose is not to nourish us but to spread their own seeds. How do they do so freely, in an oligopoly?

The ancient shared history of wheat and humanity, which began with the domestication of wild cereals by humans, continues today where it all began 11,000 years ago: in Mesopotamia. It may seem like a coincidence, but perhaps it isn’t.

The 2003 invasion of Iraq marked the beginning of the Second Gulf War when the international coalition, led by the United States, entered Iraq. The intervention was justified as a “preemptive war”, a typical “democracy export” mission. Saddam Hussein was accused of possessing weapons of mass destruction and hiding al-Qaeda militants. According to the words of then-President George W. Bush, the military mission, known as Operation Iraqi Freedom, aimed to “fight terrorism, defend the world from a serious threat, export freedom, prosperity, and secularism”. Since then, Iraq has experienced military intervention, Sunni insurgency against the central government and American forces, a civil war, the occupation of one-third of the country by ISIS (the self-proclaimed Islamic State), and, more generally, twenty years of suffering and hundreds of thousands of civilian casualties. It’s a history of our time, just like the major lie about weapons of mass destruction that never existed.

There is a name, perhaps not well-known to most, that connects the past to the present: Dan Amstutz.

One month after the invasion, Iraq was in chaos. The national seed bank in Abu Ghraib, the district where what became known as the “house of horrors” prison was located, was looted and devastated. Almost none of the 1,400 crop varieties preserved in the national genetic seed bank at Abu Ghraib survived. Since the 1970s, the Iraqi seed bank had collected and preserved a collection of the oldest domesticated seeds, a unique and precious biodiversity heritage for humanity due to the genetic characteristics contained in those seeds, which had adapted and evolved over millennia to extreme conditions of heat and drought. Only the foresight of some Iraqi scientists managed to save some varieties: wheat, chickpeas, lentils, and fruit. Seven years before the events of March 2003, they had sent a copy of these seeds to the ICARDA – the International Center for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas – in Aleppo, Syria.

Much of Iraq’s genetic heritage was completely lost, along with machinery and equipment, including seed processing facilities. In addition to the destruction of the seed bank, the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), an institution created by the United States to govern occupied Iraq, led by Paul Bremer, issued a series of orders aimed at privatizing the economy and opening it to foreign investments. These were essentially top-down orders imposed on the Iraqi people. Among these orders is Order 81 of 2004, which prohibits Iraqi farmers from saving seeds from one year to the next, opening the door to multinational corporations like Monsanto. Dan Amstutz, a former executive at Cargill (a U.S. company, the world’s largest global grain exporter), was appointed to oversee the reconstruction of agriculture in Iraq. His name was suggested by Secretary of Agriculture Ann Veneman, a former member of the International Policy Council on Agriculture, Food and Trade, which was funded by Cargill, Nestlé, Kraft, and Archer Daniels Midland. She is currently on the board of directors of Nestlé.

In the efforts to rebuild agriculture in Iraq, the Bush administration chose a figure welcomed by the agribusiness industry. Amstutz had served as an executive and president of Cargill Investor Services, a partner at Goldman Sachs & Company, Undersecretary of Agriculture for International Affairs during the first Bush administration, and the chief U.S. negotiator for agricultural matters in the Uruguay Round of the GATT, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which later became the WTO, the World Trade Organization.

To understand who Cargill is and what it does, we need to take a step back in time.

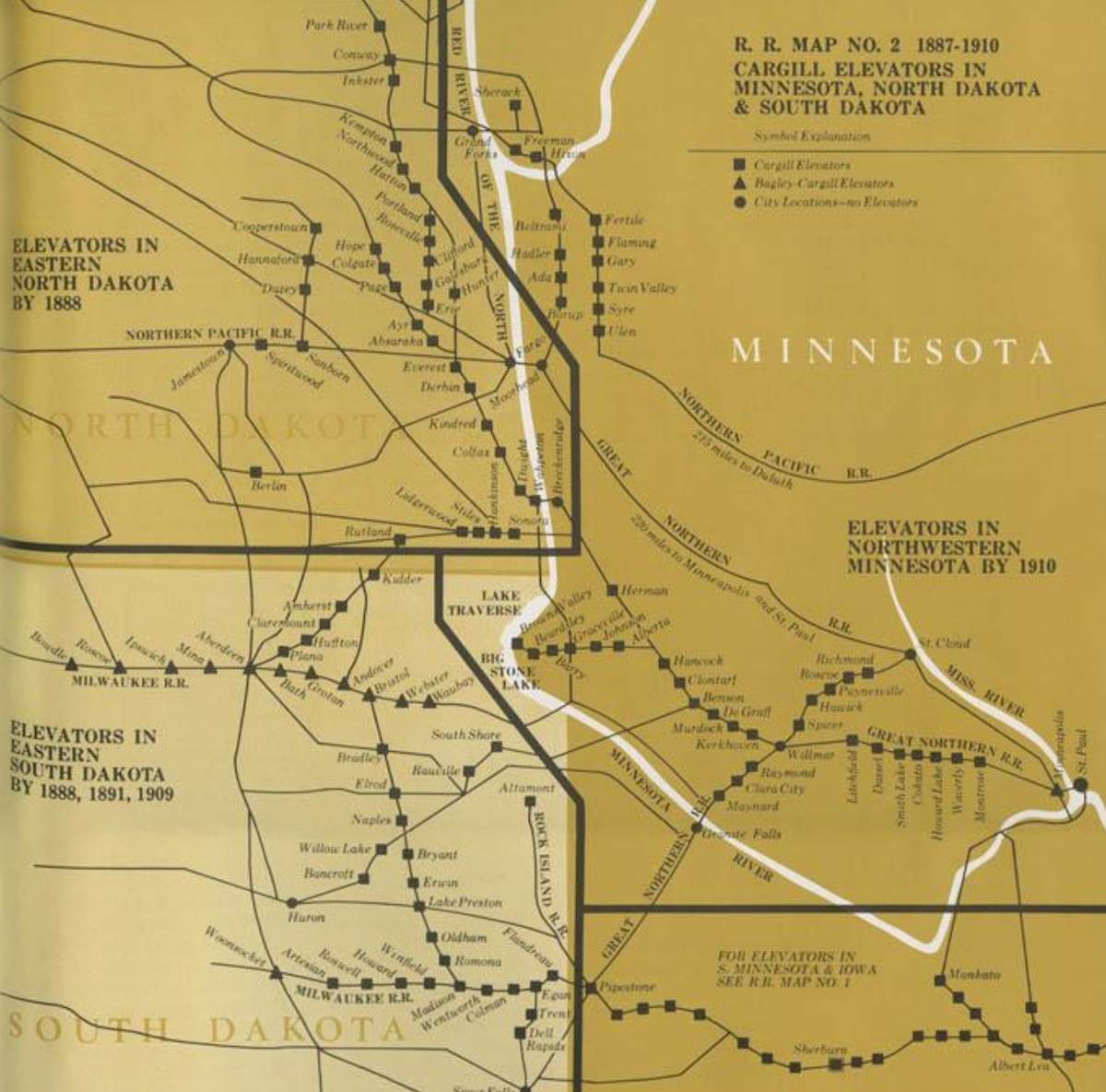

In the mid-19th century, following the conclusion of the American Civil War with the victory of the abolitionist North over the slave-owning South, there was a wave of liberation for many workers. This led to the migration of thousands of people, the discovery of new territories, and the construction of new infrastructure. William Wallace Cargill, eager to become part of the new business frontier, left his family home in Wisconsin to move to Conover, a ghost town in Iowa. It was there, in 1865, that he purchased and organized the first grain elevator next to the local railway station. Cargill offered farmers a place to store their grain, preventing it from spoiling in the field while waiting to be sold, and began buying grain directly from them after the harvest, taking a commission. Prior to his innovations, producers would go into debt hoping for a good harvest, with the risk of losing everything if their business ventures went awry. Cargill realized that the demand for grain in large cities was increasing, but the entire harvest was located in remote rural areas, often thousands of miles away from consumers. The logistics and trade of raw materials were becoming a key sector. In the following twenty years, William Wallace Cargill and his brothers followed the development of the railway network. They built, rented, and purchased warehouses and granaries in strategic locations, creating retail outlets on new routes. By 1870, Cargill had moved to Albert Lea, Minnesota, near the Mississippi River, and five years later, he relocated to the coastal corridor of Wisconsin, where he rented a large silo in Green Bay. This choice allowed for the shipment of goods to New York via the Great Lakes and the Erie Canal. By 1890, Cargill already owned around a hundred warehouses capable of storing approximately 4.3 million tons of grain. Then, overseas trade began.

With Cargill’s growth, farmers found themselves increasingly at the mercy of merchants and intermediaries. The Non-Partisan League of North Dakota began to protest the high transportation costs and the difficulty farmers faced in obtaining credit, calling for public policies aimed at “making elevators, terminals, mills, and warehouses publicly owned”. These demands garnered support from North Dakota farmers and a victory in the 1916 elections. The political program’s popularity quickly spilled over into neighboring Minnesota. With the outbreak of World War I, Minnesota became an important territory in the national grain trade. In a 1919 letter to the President of the Chicago Board of Trade, Cargill’s CEO, John MacMillan, wrote:

MacMillan’s concerns soon faded away: World War I marked the strengthening of ties between traders and the state. The demand for grains from Europe surged.

MacMillan was elected as the National President of the National Grain Dealers Association, the central organization representing the fifteen most significant grain exchanges in the United States. Cargill faced its first major scandal during World War I when it was accused of war profiteering.

By the late 1930s, Cargill was suspended from the Chicago Board of Trade, the oldest futures exchange, for improper conduct in purchasing. However, it continued to grow at a remarkable pace. In the 1920s, it initiated an ambitious expansion strategy called the “Endless Belt”, an advanced logistics system to “control the movement of grain from the moment it leaves the farmer until it reaches the final buyer”. During World War II, the relationship between Cargill and Washington intensified. The Navy entrusted the company with building ocean cargo ships, an operation that strengthened and further expanded it. Since the end of World War II, global grain exports have increased due to the growth of agricultural productivity in the United States, aided by the development of synthetic chemistry (see The Seed chapter). The Midwest became a global source of grains.

Wild plant purpose is not to nourish us but to spread their own seeds. How do they do so freely, in an oligopoly?

Between 1955 and 1965, Cargill’s grain exports increased by 400%, and annual sales reached $2 billion. By accumulating capital and with the assistance of the state, the company initiated a model of expansion, discreet but ruthless, that would make it famous. Since 1865, Cargill has become the largest privately held company in the United States by revenue, operating in 70 countries with 155,000 employees and generating $165 billion in revenue in 2022.

It is one of the world’s major suppliers of food and raw materials, providing products ranging from eggs for McDonald’s to chocolate for well-known brands, from meat to soy, from sugar to coffee, and even flour for pasta, cookies, and snacks.

The need that led to the creation of the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) was to bring together counterparties, reducing price fluctuations. Being able to establish the price for a specific commodity in advance protected against sudden price swings. The initial trades were forward contracts, which had the drawback of not eliminating credit risk since there was no guarantee that the counterparties would honor the contract. However, this was not the only problem with early forward contracts. Ownership of the contract prevented easy transfer, which significantly limited market liquidity. This limitation led to the creation of the first standardized forward contract. Subsequently, futures contracts were devised, allowing the buying and selling of a product at a specified price, even without taking delivery of the physical goods.

In reality, futures are traded by those who don’t intend to make or take delivery but want to capitalize on market movements, making it fertile ground for speculation. If there are no offsetting transactions between the buyer and the seller at the future’s expiration, the selling party can “force” the buying party to accept delivery, and vice versa. During World War I, the U.S. government was compelled to ban futures trading to stabilize prices. The ban lasted for three years but was ineffective, and prices still experienced violent fluctuations until trading resumed, at which point prices took a clear direction: they collapsed.

The U.S. government tried to regulate futures and, in 1932, enacted the Grain Futures Act, followed by the Commodity Exchange Act in 1936, which replaced the previous regulation. The aim was to curb speculators who manipulated the market through a practice known as “cornering the market”. The solution was to limit the maximum number of contracts that a single entity could keep open.

In the video, the port of Ravenna. Unloading of a ship carrying 30 thousand tons of wheat from Canada. July 2023. Images by Lorenzo Laderchi. Editing by Arianna Pagani.

Some in the industry call them “the multi”. Others refer to them as the “ABCD group”. For those not familiar with the terminology, “ABCD” stands for the world’s largest agribusiness multinationals: the U.S. companies Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill, and the Franco-Swiss-based in the Netherlands, Louis Dreyfus Company. In recent years, the list of the largest commodity traders has expanded to include the Chinese company Cofco, which became the second-largest in the world after Cargill, Singapore’s Wilmar, and Viterra, controlled by the multinational Glencore, which announced a mega-merger with Bunge in June 2023 to create another giant in the global agricultural trading business, with an estimated value of about $34 billion.

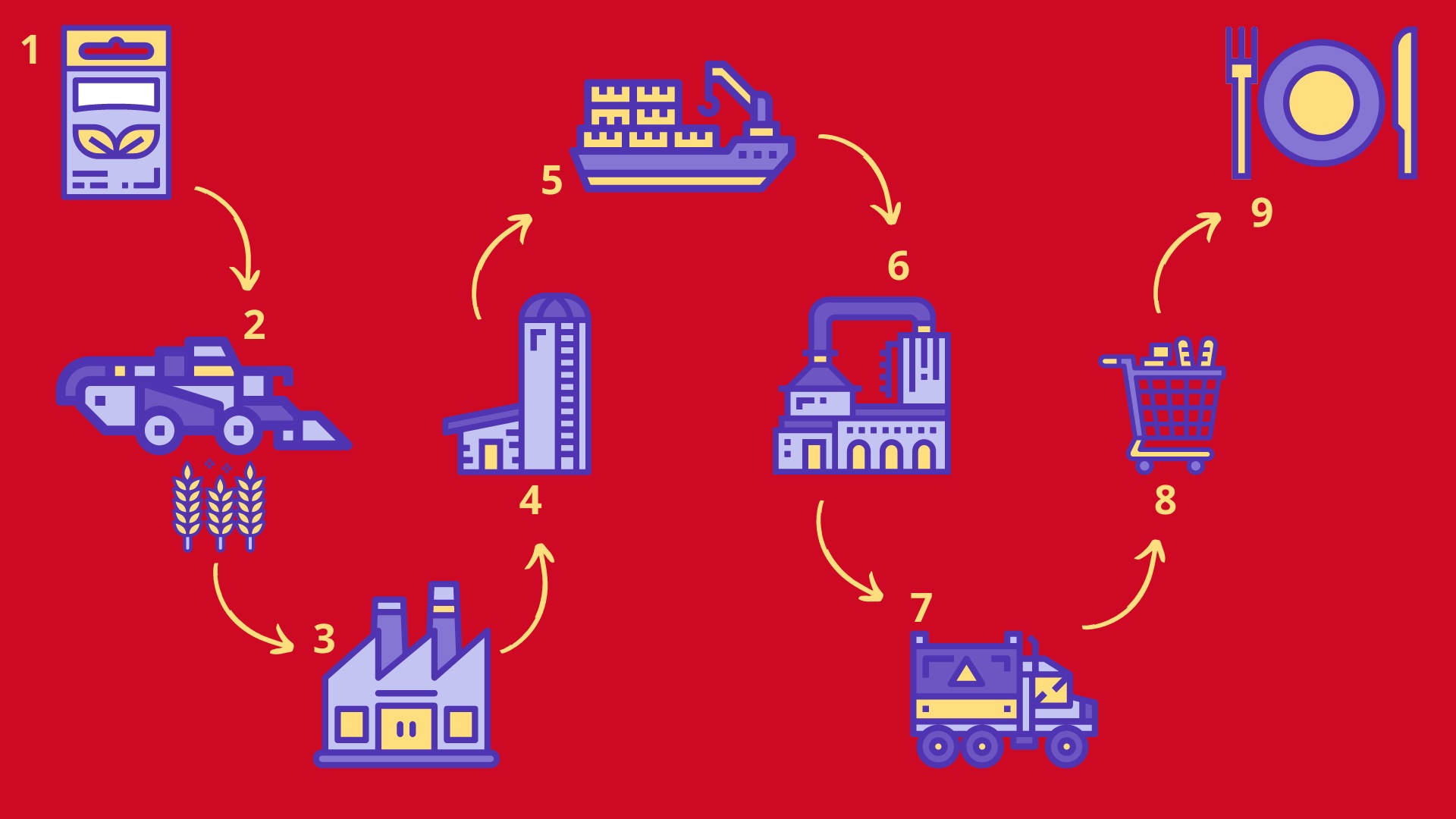

These companies are involved in buying, storing, transporting, building port infrastructure, processing, and selling food commodities around the world. In this context, commodities refer to food raw materials that are traded on the market, and they are storable and preservable over time. These are standardized, anonymous products without specific identities or connections to the regions where they are grown. They are traded in large quantities, often months in advance, and stored in warehouses, granaries, or silos before being transported on medium and large-sized ships to destinations worldwide.

Food has always traveled throughout human history, and the free market has accelerated large-scale exchanges, allowing, on one hand, greater access to a wider variety of products, and on the other, greater economic growth. However, since the 1980s, the deregulation of financial markets and the development of derivative markets have strongly influenced the exchange and pricing of commodities and essential goods, such as food. The policy choices implemented in low-income countries by international financial institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, through a series of Structural Adjustment Programs, have directed the economies of these countries towards increasing privatization, often favoring large global corporations.

Agribusiness has pushed down the prices of food commodities, pitting producing countries against each other and promoting a monoculture-based agricultural system with low-cost labor, marginalizing traditional agriculture and biodiversity. Structural adjustment policies related to debt have imposed a development model based on trade balance growth at the expense of domestically-oriented agricultural production.

Today, countries that historically produced wheat, such as Tunisia, Lebanon, Egypt, just to name a few, have abandoned a significant portion of traditional crops and are unable to meet their needs. Egypt, a country with positive population growth, for example, imports 80% of its cereal requirements since the logic of the global food factory has disrupted many internal production systems, subjecting increasingly larger areas to monoculture practices and leading to land grabbing by multinational corporations. Production is more for export than ensuring food for the residents of the territories that produce it.

As explained to Slow News by Silvie Lang, Head of the Soft Commodities Department at Public Eye, an independent non-governmental organization based in Switzerland that monitors human rights and ecosystem violations by major corporations, “Behind ABCD, there are very powerful companies that control the global trade of various commodities such as cereals, cocoa, soy, or coffee. They are highly integrated and control everything: they own plantations, have storage capacities, and control logistics. For example, Cargill has a fleet of 700 ships it uses for its operations and also for third parties. Furthermore, these giants have begun to control the processing and production sectors. In practice, they are the real managers of the value chain of agricultural commodities, which is why it is incorrect to label them as mere traders”.

According to the report published in 2022 by the ETC Group, an independent research group focused on agriculture and democratic control of technologies, the profits of these giants have surged in the last two years: Cargill alone recorded a 23% increase in revenues, reaching the record figure of 165 billion dollars for the year 2022, while Archer Daniels Midland achieved its highest profits since its foundation in 1902. “It has been calculated that since 2020, since the beginning of the pandemic, the family controlling Cargill, composed of 8 ultra-billionaires, has enriched themselves by 20 million dollars a day. While people cannot afford food, this is the company that claims to feed the world”, says Silvie Lang.

The report of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES) also highlights the concentration of power in the world trade of cereals and the lack of transparency, which translate into a supply chain that is not very resilient and subject to various shocks: the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine are the most recent example.

La segretezza dei trader è parte integrante del loro modello di business.

Slow News attempted to contact all of these multinational corporations through their press offices. They all declined the interview request. Jochen Koester, from the commodity brokerage company Agrotrace based in Geneva, agreed to speak with us. For him, as someone who works with Cargill or Dreyfus, these companies are essential for feeding the world, ensuring the transport and logistics of raw materials from one side of the globe to the other. “There is no alternative solution. These companies are necessary. They own silos, ships, warehouses because they provide a more cost-effective service. Of course, they make their profits, but that’s normal. Sometimes it is said that these large trading companies influence things. Yes, of course, they influence things. But I don’t believe they cause distortions. They are like oil companies. Do they cause distortions? Of course not!”

However, all of these companies have been at the center of environmental and humanitarian scandals (we will discuss this in the last chapter of this series), yet, despite being vital for the food supply, they are unknown to most. “Most people do not know the names Cargill, Cofco, or Bunge. Even though they are huge, even though every ingredient that ends up on their tables comes thanks to them, nobody knows them”, says Koester.

On May 5, 2023, at the Palazzo del Ghiaccio in Milan, the CEMI fair took place, one of the most important events dedicated to agrocommodities. Organized by the Granaria association and sponsored by companies like Cargill, Bunge, Viterra, CerealDocks, and Intesa San Paolo, the event saw the participation of over 600 people, including importers, brokers, traders, feed producers, processors, and mills. Out of 700 participants, only 15, at most 20, were women. The rest were middle-aged men, white-collar professionals not very inclined to speak with the media. “The market is very volatile and has become barbaric. Parallel markets have been created. In two months, prices collapsed because Ukrainian goods arrived. You don’t know what you’re buying, you don’t know what quality is coming. But all this stuff ends up in our stomachs”, explained an anonymous employee of Cofco. The multinational commodity trading companies “are very powerful” but “there are no cartels because they are very greedy companies”. Another opinion comes from an Italian employee of the U.S. multinational Bunge, the main importer of GMO and non-GMO soybeans in Italy, destined for the animal feed industry: “I know that these multinationals have impacts on deforestation, but without them, we wouldn’t have the famous hams exported all over the world, or the cheeses. Italy doesn’t have enough soybeans or corn to feed chickens and pigs, and the same goes for the wheat used to make pasta”.

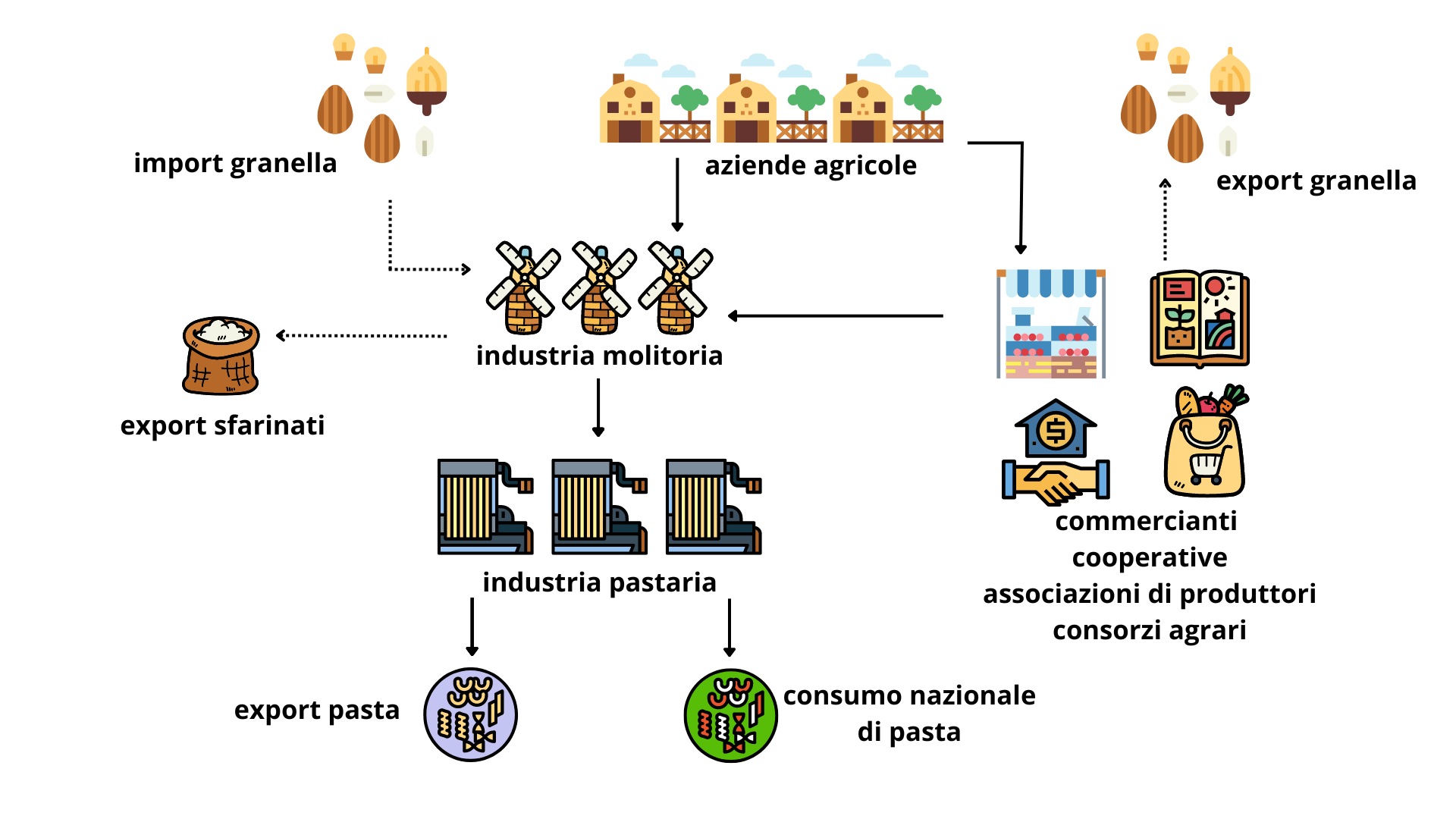

Imports and exports data help us to understand how much rhetoric there is behind “Made in Italy”: to make pasta and other products exported all over the world with the “Made in Italy” brand in Italy, in fact, it takes imported raw materials, starting from durum or soft wheat, coming from Canada, France, the United States, Ukraine, or from feed and flour to feed animals raised in the Italian agri-food districts of the Po Valley or Emilia Romagna.

The same players in the supply chain confirm Italy’s dependence on imports of raw materials. Paolo Mantovani is a partner at MantoMed, a raw materials brokerage company, with over 40 years of experience in the grain and animal feed sector. We met him at the CEMI fair in Milan: “Grain imports in Italy are used for our pasta exports. We are a country of processors, and despite political or agricultural factions continuing to talk about ‘Made in Italy,’ the truth is that we are processors, not producers”.

We are talking about the world’s best millers, charcutiers, pasta makers, and food producers, but it remains impossible to export Italian pasta made exclusively with Italian wheat.

Sandro Alberti, the president of the Granaria Association of Milan, which brings together businesses, multinationals, animal feed producers, and all actors operating in the agri-food sector, shares this opinion: “Currently, we import GMO products from Brazil, Argentina, and other countries for animal feed… It is clear that if we used GMO seeds in Italy, we would increase production, but we made a choice. I believe we cannot rely solely on foreign sources because if someone closes the Bosporus due to war, we in Italy find ourselves in a difficult situation, as has happened. Additionally, we know that financial funds are capable of significantly influencing the market by speculating on commodities, including wheat. The way to curb this speculation? In the past, there was public procurement”.

While some advocate for a more significant role of the state in managing certain commodities, others defend the maximum freedom of the market. In between, as reported in some international investigations, there are financial maneuvers that are not transparent and are not related to food production. On March 7, 2022, as wheat reached the highest price ever due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting port blockades, JP Morgan’s wealth management team encouraged clients to invest in agricultural funds and bet on rising prices. Between January 2020 and the end of 2022, specialized investment firms increased their speculative purchases in these markets by 870%, and nearly a third of the buying positions are now in the hands of investment companies. It should be noted that these entities have nothing to do with food production or marketing. “Investment companies like BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street, which also manage workers’ pension funds, have one sole objective: growth and profit maximization, and they push in that direction even with risky and opaque maneuvers”, explains Pat Mooney, an expert on agricultural diversity, biotechnology, co-founder, and executive director of the independent research group ETC. “These companies have also stated that they want to withdraw from climate change commitments because they cannot guarantee profits to shareholders. But while they make profits, thousands of people die of hunger”.

In 2022, the world recorded the highest inflation rates in the last 40 years, with food price inflation even higher. In March 2022, the FAO Food Price Index reached a value of 159.7, and although international food prices are decreasing, they remain at their highest levels ever.

In recent years, supply chain disruptions have been attributed to various factors: rising prices, the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and interruptions in the supply of oil, gas, fertilizers, and essential goods, as well as the recurrence of extreme weather events that have compromised food production worldwide.

However, even with adequate food production and inventory levels meeting global demand, along with the decline in international oil and gas prices between 2020 and early 2023, the overall food price index remains 14% higher than in 2021. This points to a structural crisis within the global industrial agri-food system, which is too concentrated, financialized, and highly specialized. The current industrial food system has proven highly inefficient in addressing the energy, health, environmental, and food challenges of our time: it relies on the use of petroleum and gas, depends on large volumes of pesticides and fertilizers used in monoculture cultivation and long-distance transportation, all necessary for the operation of this global food machine.

Unloading of grain at the port of Ravenna. June 2023. Video by Giuseppe Pellegrino.

The port of Ravenna is the largest cereal and raw materials port related to livestock and agribusiness in Italy. Here, seeds, cereals, and flours from all over the world arrive. On a sweltering morning in early July, docked at the Docks Cereali Spa, the largest terminal in the Mediterranean for the storage and handling of dry goods, including cereals, is a ship loaded with 40,000 tons of wheat from Canada, half destined for Barilla and half for the multinational Viterra. “It’s high-quality wheat”, says Roberto Rubboli, one of the temporary company managers and former president of the port company. “It’s wheat that meets the specific requirements of the industry, namely the standardization of the product”.

It takes about six days to unload it. Dozens of trains and hundreds of trucks are ready for logistics: each train can carry about 1,000 tons of goods, and each truck can transport 30 tons. These vehicles will reach mills, farms, and processors. The port of Ravenna has historical significance, especially related to poultry companies like Aia and Amadori, pig farming, and, of course, pasta production.

From Canada and other countries like France, Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, wheat arrives, which will be transformed into pasta. In turn, pasta will be packaged and exported to the other side of the world: a globalized industrial agricultural system based on monocultures, abundance, food waste, and food standardization. Food that, according to some, “feeds the world”: the FAO reminds us that hunger affects 735 million people, 122 million more than in 2019.

Between 2007 and 2008, the increase in food commodity prices, especially cereals, caused a food crisis: protests against “expensive food” erupted in Egypt, the Philippines, Cameroon, Haiti, leading to the Arab Spring of 2010-2011.

And today?

Fifteen years later, little has changed: the agri-food sector remains in the hands of a few players with immense economic and political power, antitrust laws are inadequate to recognize and limit this power, and the policies of the last 30 years continue to impoverish and make many countries in the Global South dependent on imports.