Il Made in Italy è conservazione del potere

Il Made in Italy è solo fumo negli occhi: la chiamano sovranità alimentare ma è conservatorismo malcelato.

Wild plant purpose is not to nourish us but to spread their own seeds. How do they do so freely, in an oligopoly?

The Wheat Library houses 120 varieties of traditional and modern wheat from around the world. This year it has the shape of a labyrinth because, as Antonio Pellegrino explains, “in this meaningless contemporaneity we must get lost to find ourselves united”.

Caselle in Pittari (Sa), April 2023.

If there is a place where this story of wheat and humanity has its origin, it is undoubtedly in Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. In this region, known as the Fertile Crescent and now encompassing Iraq and Syria, the special connection between Homo sapiens and plant species, marked by coexistence, dependence, and domination, begins.

Between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago, in this region abundant with wild cereals, humans initiated the so-called domestication process, transforming wild plants into domesticated ones. They selected the finest ears of grain in the fields, picked specific varieties and seeds with characteristics they preferred for their needs, and preserved them for the next year’s sowing.

In the previous millions of years, wild species had evolved and reproduced entirely independently and with entirely different goals: wild plants do not aim to nourish us but to spread their seeds.

Through the process of domestication, humans entered the history of these plants, acquiring an “evolutionary responsibility”, to use an expression coined by Sir Otto Frankel, a plant geneticist who had been warning about the loss of biodiversity in agriculture due to human activities since the 1960s.

Intuitively or unknowingly, humans began to contribute to the improvement of the characteristics of food plants they found useful. They effectively conducted genetic improvement. Since then, the evolution of cereals and agriculture has been closely tied to that of humanity.

From the domestication of wild emmer wheat, the transition led to einkorn wheat (Triticum monococcum), and from this modest einkorn wheat, the most well-known and commonly used grains in daily diets emerged: durum wheat, primarily used for pasta and pizza, and soft wheat for pastries.

Thanks to the domestication and cultivation of cereals, humans shifted from a nomadic lifestyle to a settled one. They constructed granaries to store grains, and these granaries, along with the surrounding walls to protect the harvest, gave rise to the first ancient urban settlements.

The earliest cities such as Ur, Eridu, or Uruk were born this way, and with them, the ownership of grain was concentrated among the nobility and priests. The granary became the basis of power, and whoever possessed the grain had power. But with grain, a unit of measurement, numbers, and writing were also needed. “We are made by cereals, and cereals are made by us”, Åsmund Bjørnstad wrote in the book “Our Daily Bread: A History of Cereals”. Indeed, it is true.

Great human civilizations, such as the Sumerians, Assyrians, Egyptians, and the Indus Valley, emerged on the basis of expanding agriculture, mainly based on cereals. The Neolithic agricultural revolution marked an unprecedented turning point in terms of human well-being and the alteration of relationships with the surrounding environment, which was inevitably changed by agriculture and human activities.

As the environment changed, the seeds of cereals moved and spread freely, migrating to all continents along with humans, evolving with the kind of selection carried out by farmers themselves.

For thousands of years, genetic improvement and the evolution of crops occurred in this manner: by selecting the “best” plants from the many growing in the fields, without patents or royalties. This continued until the late 19th and early 20th centuries when, with the discovery of genetics and the laws of heredity formulated by the Augustinian friar and biologist Gregor Mendel in 1866, everything changed.

The traditional techniques of mass selection (which involved collecting the seeds of the best plants, without separating them but mixing them) inherited up to that point were partially replaced by selection through artificial genetic improvement techniques (pure line or genealogical selection), especially through the crossbreeding of different varieties to obtain new cultivars.

Cultivar is a term used in agronomy to refer to a cultivated plant variety obtained through genetic improvement, which encompasses a set of specific morphological, physiological, agronomic, and commercial characteristics of particular interest and can be passed on through propagation, both by seed and by plant parts.

In the early 20th century, in Italy, two of the most important pioneers in the genetic improvement of cereal plants and scientific “rivals”, Francesco Todaro and Nazareno Strampelli, agronomists and researchers at public universities and research centers, were both committed to improving Italy’s critical economic situation through agriculture. During those years, a significant portion of the Italian population relied on outdated and subsistence farming, lacking adequate agricultural tools and technologies.

This dependence was also due to the so-called “feudal remnants”, borrowing the words of economic historian Emilio Sereni, which were still deeply entrenched in the Italian land ownership system. The vast majority of land was owned by a few landowners, often nobles, the clergy, large landholders, and local power brokers who focused on agricultural income and had no interest in investing in and improving the living and working conditions of the millions of sharecroppers, laborers, and day laborers working in the Italian countryside.

During those years, however, the imbalance between agricultural consumption and production, along with population growth, led to increased imports of wheat from abroad, which significantly impacted the trade balance. The situation worsened with the outbreak of World War I and the subsequent conscription of laborers to be sent to the front lines, leading to a mass exodus from the farms.

The Wheat Labyrinth. Giuseppe Pellegrino, April 2023, Caselle in Pittari (Sa).

At the Experimental Station for Grain Cultivation in Rieti, central Italy, thanks to the establishment of a complete supply chain that goes from research to the commercialization of seeds, Strampelli initiated a program of genetic improvement of wheat that would lead to the development of dozens of varieties of soft and hard wheat. These varieties were destined to revolutionize Italian wheat farming in the first half of the 20th century and global wheat cultivation in the subsequent decades.

In 1914, he introduced “Carlotta Strampelli” wheat (named after his wife and collaborator, Carlotta Parisani), obtained through hybridization and capable of simultaneously resisting rust and lodging. The following year, in Foggia city, he produced “Senatore Cappelli” durum wheat, which had come back into “fashion” in Italy in recent years and was tied to some controversies regarding its exclusive concession to the SIS seed company (we will revisit this issue later).

Strampelli particularly excelled in the genetic improvement of soft wheat through the creation of early varieties, such as the famous “Ardito” and “Mentana”, achieved through a “three-way cross” between the wheat varieties “Wilhelmina”, “Rieti”, and the Japanese “Akakomugi”. In simplified terms, the agronomist from the Marche region crossed the “Rieti originario” variety, resistant to rust, with Wilhelmina Tarwe, a high-yield Dutch variety. He then crossed the result with “Akakomugi”, a Japanese wheat of limited agronomic importance but characterized by its short stature and early maturity.

Through these crosses, he obtained new varieties with innovative characteristics that allowed for increased wheat yields with only a modest increase in cultivated acreage. Strampelli’s work culminated in the early 1920s with the release of the famous “Grani della vittoria” or “Chosen Races”, which became a powerful propaganda tool for the Fascist regime during the “Battle for Grain” in 1925.

Mussolini turned it into a propaganda operation for the Fascist regime, connecting it with the myth of autarky. However, it was due to the innovative work of public research and its scientists, such as the work done by Strampelli, that wheat production doubled. Italy went from producing 44 million quintals of wheat in 1922 to 80 million quintals in 1933, thereby securing popular support for Mussolini. This was a work of public research and innovation that was not “national” in identity but was based on the crossbreeding of traditional wheat varieties with plants from all over the world, including Japan, Tunisia, and the Netherlands.

Following the Battle for Grain, while Italy reduced its dependency on foreign wheat, its reliance on synthetic fertilizers and machinery began to grow. The years between the two world wars coincided with the commercialization of fertilizers based on ammonium nitrate. The synthesis of ammonia was patented by the German chemist Fritz Haber, who, in 1909, along with Carl Bosch, a researcher at the chemical company BASF (remember this name, as it will come up again), developed the industrial process that began in 1913. Haber was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1918 for this discovery, while Bosch, together with Friedrich Bergius, received it in 1931 for their work on chemical synthesis under pressure (beginning with the ammonia synthesis).

The discovery of ammonia synthesis is considered one of the most important achievements of humanity because it allowed for the production of explosives and, at the same time, inexpensive and large-scale synthetic nitrogen fertilizers. It’s no coincidence that Strampelli’s variety “Ardito”, named in honor of the assault troops of World War I, achieved success in part due to the use of ammonium nitrate, which the Germans used in explosive devices.

During the war, it was observed that ammonium nitrate released nitrogen into the soil, making plants more vigorous. Varieties like Ardito, as well as subsequent modern varieties, could tolerate a higher nutrient input from the soil. In other words, they could be cultivated on well-fertilized lands because they could withstand lodging, the collapse of the stem, due to the increased weight of the grain resulting from the higher nutrient accumulation from the soil.

War industries, including BASF and Bayer, were used both in World War I and World War II to produce military materials, including explosives and chemical weapons. After the wars, they were converted to produce fertilizers for industrial agriculture. Even today, ammonium nitrate is one of the main components of synthetic fertilizers used in soils, which Russia ceased to export in February 2022 before invading Ukraine. In other words, the connections between wheat and war have been prevalent throughout history and continue to exist today.

The term “rust” refers to plant diseases caused by pathogenic fungi of the Puccinia genus, resulting in the formation of rust-colored lesions (pustules) that can affect various parts of the plant, such as the stem, leaves, and spikes, depending on the fungal species involved.

“Lodging” is the tendency of tall, herbaceous plant species to bend or lean, sometimes even reaching the ground. This characteristic is often influenced by severe weather events such as heavy rainfall and strong winds, but in the case of wheat, it can also be attributed to excessive spike fertility.

“Senatore Cappelli” is the first variety of durum wheat developed by Strampelli through selection from a Tunisian population called Jean Retifiah. It is a medium-early cycle variety with tall growth, a large white spike with long black awns, large vitreous kernels, good hectoliter weight, and a high protein content. This variety was dedicated to the politician Raffaele Cappelli, who provided land for agricultural experiments aimed at creating wheat varieties suitable for the hot and arid climates of Southern Italy.

Among the fascist regime mottos, we can recall phrases like “the plow makes the furrow, but it’s the sword that defends it” or “the deeper the furrow, the higher the destiny.” These slogans reflect the propaganda and ideals of that era.

Starting from the post-World War II period, Strampelli’s wheat varieties spread widely on an international scale in the genetic improvement programs implemented by major wheat-producing countries, including China, Argentina, Mexico, Mediterranean and Eastern European countries, the Soviet Union, as well as Australia and Canada. In Mexico, in particular, the “Mentana” variety formed the basis of the genetic improvement program that allowed the American agronomist Norman Borlaug, now remembered as the father of the Green Revolution, to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, more than forty years after Strampelli’s work.

The genes introduced by the Italian agronomist in his wheat varieties, responsible for the short stature of the stem, early maturation, and resistance to rust, still form the genetic basis of “modern” wheat varieties cultivated worldwide. However, Strampelli’s stroke of luck or genius was his focus on the concept of biodiversity a century ago, using wheat varieties from all corners of the globe for experimental purposes.

As recounted by Sergio Salvi, a biologist, expert in agri-food history, and biographer of Nazareno Strampelli, “In an era when the concept of genetic diversity had not yet emerged, he assembled a collection of 250 wheat varieties from around the world to have the maximum diversity possible in terms of useful characteristics to combine through crosses, generating new varieties more suitable for his purposes. Thinking today of relying solely on monoculture or a handful of agricultural species or varieties to produce more sustainably is a utopia: genetic diversity in agriculture is essential for progress in yields and overcoming climatic and environmental challenges”.

Meanwhile, with the advent of “modern” genetic improvement, fundamental changes have occurred in the realm of seeds. Improvement has transitioned from agricultural fields to research stations, moving from the hands of farmers to those of researchers, and in the process, reducing the variety of climates, soils, and cultures in which selection takes place. Research stations have become increasingly similar to each other over time and less like farmers’ fields. The selection that once aimed at specific adaptation to each context, place of cultivation, and dietary culture of a particular region has been replaced by selection for the broadest possible adaptation to environments “adjusted” through external chemical inputs, thus making them more similar and standardizing dietary cultures as well.

This process has produced high-yielding wheat varieties, among others, which have partly met the growing demand for food. However, at the same time, this transformation has led to what Riccardo Bocci, an agronomist and technical director of Rete Semi Rurali, a network of associations focused on the protection, enhancement, and promotion of agricultural biodiversity, refers to as the “deskilling of farmers”. “This type of agriculture has taken away skills and the ability of farmers to understand the environment. It offers a ready-made technological package where seeds are an important part of this technological package. […] This type of agriculture has spread across the planet, reducing biodiversity, destroying habitats, ecosystems, and dietary cultures” explains Bocci.

While for thousands of years, plant genetic improvement was in the hands of farmers, in the last forty years, it has increasingly shifted towards private companies that finance their activities through seed sales licenses. This transition has been facilitated by the adoption of hybrid seeds, which have made farmers dependent on a few major seed companies, from which they need to repurchase seeds and chemical inputs every year.

Inside a warehouse of a French agricultural company, in Bourgnogne, in eastern France. The company is part of the Dijon Cereals cooperative, together with 3800 farmers who contribute directly to the cooperative, supplier of Barilla-Mulino Bianco. The farm’s warehouse contains certified seeds and plant protection products, herbicides, and chemical synthesis products used in agriculture. March 2023. Video by Sara Manisera.

However, the work of both public and private seed companies has been and continues to be of paramount importance in innovating agriculture. Some of the most significant companies in Italy were established as early as the beginning of the 20th century, driven by researchers and scientists from public universities.

Consider, for instance, the “Società Anonima Cooperativa Bolognese”, now known as the Società Produttori Sementi (SIS), founded in 1911 under the leadership of Francesco Todaro, a professor of agriculture and the Director of the Higher Agricultural School of Bologna, with support from the Bologna Savings Bank. Another example is the National Institute of Cereal Genetics established by Nazareno Strampelli, or the Agronomy Institute at the University of Agriculture in Florence, led by Marino Gasparini, which developed the Verna variety suitable for the Apennines and more marginal mountain areas.

Furthermore, there’s CREA, the Council for Agricultural Research and Economics, Italy’s most important public research institution, with its roots dating back to the time before the Risorgimento. It began with the establishment of the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce of the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1850, under the leadership of Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, who was not only a statesman but also an agricultural entrepreneur and the founder of Italy’s first fertilizer industry.

Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, in the years 1850-52, as the Minister of Agriculture and Commerce, traveled between France, Belgium, and England, where he came into contact with various agricultural practices, including the use of guano as a fertilizer. Guano, consisting of seabird droppings, is found in large quantities on some South American islands and coasts. It was known for its potent organic fertilizer properties, composed of ammonium oxalate and urate, phosphates, as well as some mineral salts and impurities. Cavour recognized its effectiveness and promoted its importation. However, the price of guano increased significantly due to growing demand. The Count decided to involve chemists Domenico Schiapparelli and Bernardo Alessio Rossi in creating a factory for artificial guano.

What has happened in the last forty years, both globally and nationally, is a concerning concentration of the seed and agricultural technology market in the hands of a few companies, along with the gradual dismantling and defunding of public genetic improvement programs.

In practice, private companies now decide which seeds to improve, develop, and for what purpose. Those who control the seeds also control agricultural and food systems, which means they have a say in what we grow and eat.

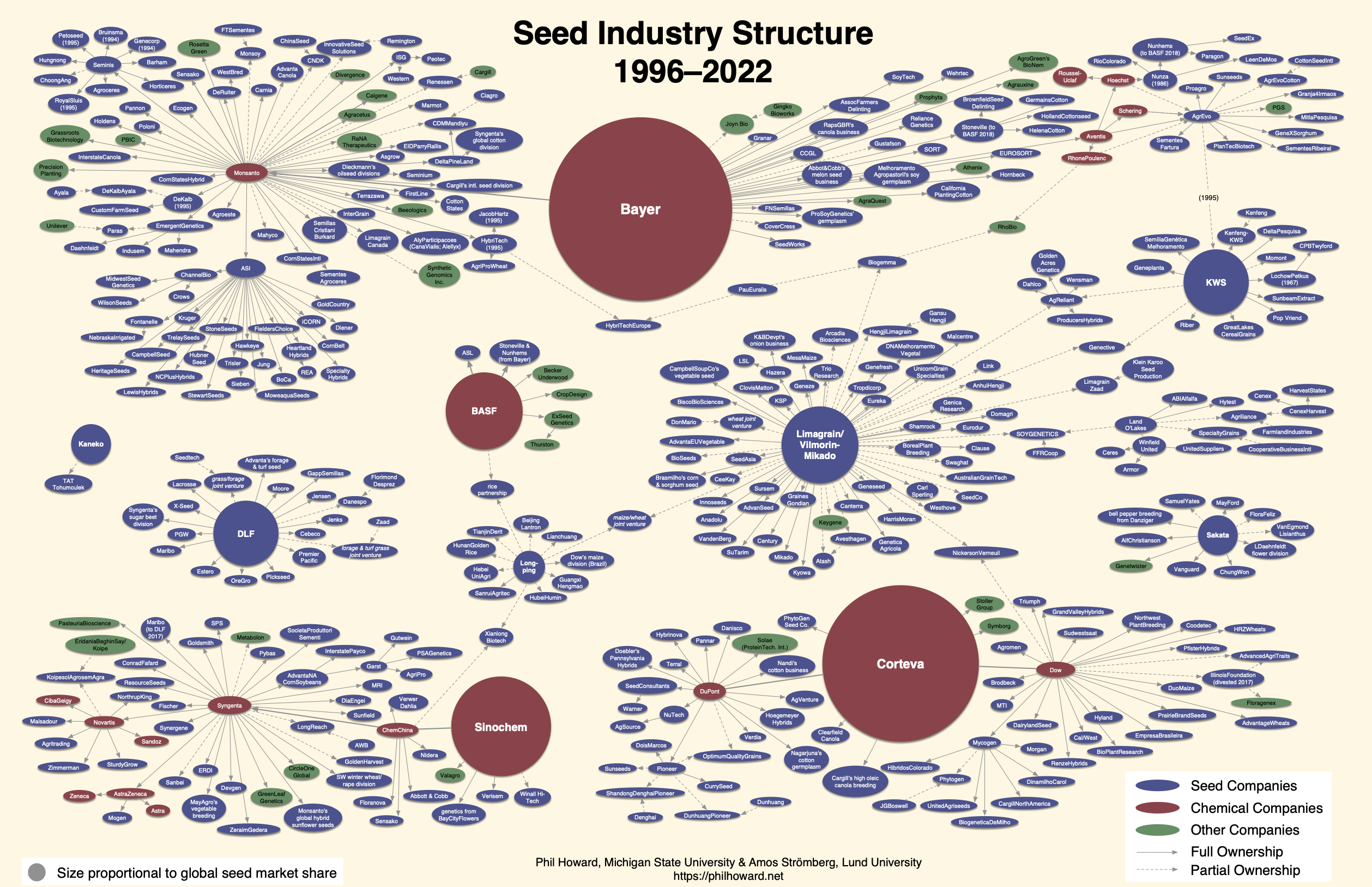

At the time of writing, seed sales are controlled by a small number of companies. Bayer-Monsanto (German), Dow-DuPont-Corteva (American), Sino-ChemChina-Syngenta (Chinese), and BASF (German) dominate 60% of the global seed market and 75% of the global pesticide market. Between 2018 and 2022, the “big four” agrochemical companies, Bayer, BASF, Corteva, and Sinochem, further increased their power through acquisitions and tactical mergers. The mega-merger of Sinochem and ChemChina in 2021 marked a significant shift in the agri-food system. The merger of two giant state-owned Chinese companies resulted in the creation of the world’s largest chemical conglomerate and the third-largest seed company, operating under the name of the Swiss giant Syngenta, which was acquired in 2017.

Phil Howard, a professor at the University of Michigan and a member of the independent research group IPES – International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems – which focuses on food system research and sustainability, writes, “In the 2000s, seeds and agrochemical products were controlled by six companies. Today, the number has been reduced to four. This trend has blurred the boundaries between seeds, agrochemical products, technologies, and digital agriculture, all controlled by the same large companies”.

Pasquale De Vita from CREA, the Council for Agricultural Research and Economics based in Foggia, believes that “For much of the last century, research activity was almost exclusively a public affair. Today, however, technologies, including the most debated ones like genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and others, are in the hands of private companies. Instead, we believe they should also be governed by the public. Technological innovation is essential in the public sector because it can help the farm be more free from certain commercial strategies that create dependency. If you close off the public’s ability to use even the most modern technologies, clearly someone else will do it in your place”.

On March 14, 2023, CREA, the Italian government’s agricultural research agency, presented a document together with Assobiotec, a branch of Federchimica that brings together about a hundred companies in the biotechnology field, regarding the contribution of advanced genetics. They concluded that there is a need to “promote a public-private system of genetic improvement based on advanced genomic technologies”, considering it “strategic to adapt national agriculture to the future and maintain the sustainability and competitiveness of the national agricultural sector”. Consumer representatives, farmers, and civil society were notably absent from the presentation.

A portion of civil society views this transition as premature and harmful. The “Coalizione Italia Libera da OGM” (Italy Free from GMOs Coalition), composed of 32 associations of farmers, environmentalists, and organic consumers, expressed concern in response to the announcement of two bills allowing field experimentation of Assisted Evolution Techniques (TEA) to be approved by autumn 2023 without waiting for possible European regulations. The Coalition stated that “it is serious that a public institution that should provide farmers with guidelines based on a solid and in-depth documentary basis is promoting industrial interests, in an obvious conflict of interest”.

For the associations of the “Coalizione Italia Libera da OGM”, the position of CREA and the industry is based on “an anti-ecological and anti-social political vision, crushed by the interests of seed and agro-industrial companies”, and they call on politics “to choose the safe path for everyone: public research must be funded and carried out, but it must be transparent, demonstrating the risks of technological innovations”.

The public debate in Italy on these technologies has often been polarized in recent years and has not allowed room for reflection and quality discussion. What is certain is that GMO maize and soybeans cultivated in Brazil, Argentina, Canada, or the United States have already entered the Italian and European food supply chain for years in the form of feed for cattle, pigs, poultry, and fish, as Italian production is not sufficient to meet the dietary needs of these animals and this industry. The other certainty is that, at present, four mega-companies control over 50% of a very important market, one that encompasses seeds, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, technologies, and food.

In the “Food Barons” report, published in 2022 by the ETC Group, an independent research group focused on democratic control of technologies, it is stated that “Food Barons are introducing a series of new technologies and “techno-fixations” that are conceived and designed to further strengthen corporate control over food, nutrition, and agriculture. They already control agricultural research and development to meet their own interests and continue to concentrate power and influence trade, aid, and agricultural policies to fuel their growth and profits”.

The issue is not the technology itself but who controls and has power over that technology. Phil Howard is clear: “This is effectively an oligopoly because when four companies control over 40% of the market and have control of the technology, it is no longer competitive and is not oriented toward the public interest”. So, perhaps, wouldn’t it be better to govern these technologies at the public level, provide proper information that includes all stakeholders, and prevent even new innovations from being controlled by a few private entities?

If on a global scale, four multinational corporations control the market for seeds, pesticides, and technologies, Italy is also witnessing, albeit to varying degrees, a growing vertical integration of the supply chain, from seeds to pasta and supermarket products. This was extensively covered in the Altreconomia investigation titled “BF: The True Ruler of Agriculture in Italy”.

In a nutshell, the Italian agro-industrial supply chain has transformed around BF Spa, the most significant Italian agro-industrial group, listed on the Milan Stock Exchange. It is managed by Federico Vecchioni, a former president of Confindustria. This group has absorbed all key sectors, including seeds through SIS (Società Produttori Sementi), land ownership with Bonifiche Ferraresi (the largest landowner with around 11,000 hectares), the marketing of inputs and agricultural services with Consorzi agrari d’Italia Spa, and even extends to large-scale organized distribution with the Stagioni d’Italia brand. But that’s not all; BF has also signed a collaboration agreement with Eni, with Coldiretti’s support, to develop crops for energy use in Italy.

On paper, these operations are meant to strengthen Italian agriculture against multinational corporations, make it competitive, and defend the “Made in Italy” brand. As Stefano Ravaglia, head of research and experimentation at SIS, explains, building an integrated vertical supply chain “allows you to sit at the globalization table: this way, you can negotiate better with these partners who have enormous investment capabilities, even in research”. However, according to Riccardo Bocci of Rete Semi Rurali, this vertical integration of the supply chain from seed to supermarket product “takes power away from the farmers who disappear behind the supermarket brands and forces them to adhere to an exclusive club with rules. If you don’t comply with these rules, you can’t use the seeds. We saw this with the Senatore Cappelli wheat variety entrusted to SIS under a monopoly by Crea and then penalized by the Antitrust for its illegitimate practices against farmers who wanted to sow the Senatore Cappelli durum wheat variety”.

The Senatore Cappelli case is emblematic. In 2016, Crea assigned the exclusive rights for certified Senatore Cappelli seed commercialization to the Società Italiana Sementi (SIS) under a regular licensing agreement. However, the company engaged in a series of unfair business practices towards farmers: unjustified price increases, delayed or denied supplies, and mandatory returns of the wheat produced by cultivators. This is why the Antitrust decided to fine SIS with a €150,000 penalty for creating an imbalance in business relationships within the agri-food supply chain.

But there’s another reflection that should be made in a moment when there is so much talk about Italian agriculture, food sovereignty, and “Made in Italy.” As Duccio Facchini, director of Altreconomia, explains: “From 2010 to 2020, we lost 400,000 agricultural businesses. 30% are mainly run by the elderly. There is a lack of innovation, and we continue to import raw materials to make products that are exported with the ‘Made in Italy’ label. We think we produce wine, Parmesan, cured meats, and pasta, but we import most of the products needed to make them. This rhetoric of ‘Made in Italy’ and food sovereignty, in reality, defends a power block and an agricultural model based on oil, pesticides, and imports”.

This power block opposes all new technologies—just look at the opposition to lab-grown meat from Coldiretti, Federico Vecchioni, BF’s president, and even Agriculture Minister Francesco Lollobrigida, who presented a law to ban its production but not its importation. It opposes public control over them. This power block, by appropriating the term “food sovereignty”—a definition coined in 1996 by La Via Campesina—does not protect and strengthen small and medium-sized businesses that ensure quality and biodiversity in mountainous and hilly areas, the true backbone of Italy. Instead, it aims to defend the current industrial model of agriculture, old and polluting, which is among the main contributors to the ongoing climate crises.

Il Made in Italy è solo fumo negli occhi: la chiamano sovranità alimentare ma è conservatorismo malcelato.

While seeds and food have been increasingly transformed into standardized and homogenized products controlled and developed by a few, there are those who continue to protect and promote agricultural and food biodiversity. They are building diversified agricultural systems where seeds are not just a technical component but also serve as social, anthropological, and symbolic links. This is happening in Caselle in Pittari, in the Cilento, Alburni, and Vallo di Diano National Park, where the Monte Frumentario social cooperative has established a local supply chain that goes from seeds to flour, pasta, and bread. They have also created a grain library, a field that resembles a maze this year and contains 120 varieties of traditional and modern grains and blends from around the world.

The Wheat Labyrinth. Giuseppe Pellegrino, April 2023, Caselle in Pittari (Sa).

It’s also happening in Sicily with Simenza, the Sicilian farmer seed company, a cultural association founded in 2016 to protect and promote agrobiodiversity through the creation of short supply chains and sustainable distribution systems. Or in Tuscany with the Florriddia farm, or in the Oltrepò Pavese, and even in the Marche, Abruzzo, and Veneto. These are the true guardians of seeds, all associated with Rete Semi Rurali, who practice biodiversity and innovate in the environments where seeds are grown. It’s a completely different approach that embraces local communities, the environment, and revolutionizes the way food is grown and distributed.

“The discoveries we see with epigenetics, how the environment and the genome influence each other, represent a change in the genetic dogma. If the environment affects the DNA of seeds and these characteristics can be passed on to their offspring, then the work we do becomes even more important because this would mean that the environment in which I grow seeds has an influence on their evolution and genetic improvement” explains Riccardo Bocci of Rete Semi Rurali. For him and the people in this network, technology alone cannot be the answer to the climate, social, economic, and existential crisis society is currently facing.

And seeds themselves cannot only respond to economic needs and interests. “For us, the seed is an excuse to talk about something else. For example, how do we increase the abilities of farmers, how do we distribute food, how do we manage the land, the soils, and common goods in a decentralized and community-based way to meet not only economic needs but also ecological and community care needs. Behind a seed, there is much more than just a technical component. There is a history, an imagination, connections to the environment, people, and territories. In the bigger picture, there is a political vision of building a different economy”.

This work was conceived and created by Sara Manisera, Bertha Foundation Fellow 2023, with the support of Bertha Foundation, and produced by Slow News.

Video operator: Giuseppe Pellegrino

Illustrations: Vito Manolo Roma

Un podcast settimanale per approfondire una cosa alla volta, con il tempo che ci vuole e senza data di scadenza.

È dedicata all’ADHD e alle neurodivergenze. Nasce dall’esperienza personale di Anna Castiglioni, esce ogni venerdì e ci trovi articoli, studi, approfondimenti, consigli pratici di esperte e esperti.

La cura Alberto Puliafito, è dedicata al giornalismo e alla comunicazione, esce ogni sabato e ci trovi analisi dei media, bandi, premi, formazione, corsi, offerte di lavoro selezionate, risorse e tanti strumenti.

La newsletter della domenica di Slow News. Contiene consigli di lettura, visione e ascolto che parlano dell’attualità ma che durano nel tempo.

The image of Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, is a reworking by Slow News starting from the portrait of Antonio Ciseri (1821-1891) – Public domain