The seeds

Wild plant purpose is not to nourish us but to spread their own seeds. How do they do so freely, in an oligopoly?

There is nothing similar in Nature, but our flours are increasingly standardized.

The third stage of this journey along the wheat supply chain continues with the other two major protagonists in the history of humanity: the mill and its miller. Alongside the process of wheat domestication and selection that began in Mesopotamia, humans began to devise ways to crush, consume, and reduce grains to flour using pestles, mortars, and other manual tools. Grinding the harvested wheat has always been a serious problem that required a significant amount of effort and labor. From stones, the process evolved into the first prehistoric mills – a “plate” of rock on which wheat grains were crushed by hand. From these, the first rudimentary mills with two overlapping stones developed. Technological evolution then led to the development of hand mills, animal mills, windmills, and water mills. As French historian Marc Bloch writes in Land and Work in Medieval Europe, “it was the mill that created the miller”.

If, in the past, it was women or slaves who took care of flour preparation, with the mill, everything changes, and it becomes a symbol of power. The miller thus becomes the central figure in the community’s economy because he represents the link between agricultural production and the subsequent stages of grain transformation into flour, for both human and animal consumption. While during the Roman period, the operation of mills was entrusted to slaves, starting from the medieval period, mills were constructed by local lords, municipalities, or free cities, and the miller represented the figure entrusted with the task of managing and overseeing the mills. During this period, millers were therefore rural workers dependent on secular or ecclesiastical power. However, in reality, whoever controlled the mill also had direct control over the income of every citizen because they knew the quantity of grains that each person brought for grinding.

For hundreds of years, the miller’s figure has been that of a guardian of a complex yet essential knowledge for the entire “civilization of wheat”, inseparably linked to the peasant world. With the advent of the roller mill at the end of the nineteenth century and the industrial roller mill, a radical change occurs. As the Italian Association of Friends of Historical Mills writes, “the rapid transformation of the artisanal mill into a multi-story mill-factory capable of feeding entire inhabited centers has led to a progressive abandonment of mills from the past, and the old millers were gradually induced to abandon the ancient work, which was no longer competitive”.

While it is true that factory mills have had the merit of feeding increasingly populous urban centers, they have marked a gradual detachment from rural civilization and local agriculture. The mill that distances itself from the field, the production of food that moves further away from the place where the food is consumed. And the food itself, namely wheat and flour, undergo changes to adapt to the needs of the factory mill.

To understand it, once again, we need to start from the grain of wheat. And see what happens inside an industrial mill.

Let’s start with an initial distinction between durum wheat and soft wheat, both used for human consumption. Soft wheat has grains, or kernels, that are soft and round; durum wheat has elongated grains with a harder consistency. Soft wheat yields flour mainly used for bakery products, sweets, and the production of bread and pizza. Durum wheat, on the other hand, produces semolina, primarily used for pasta, whether dry or fresh, and occasionally for bread (for example, Altamura bread). Soft wheat is the most widely used globally, representing about 90% of exchanges. Durum wheat, on the other hand, is more niche, less cultivated, and used to a lesser extent, primarily by the pasta industry.

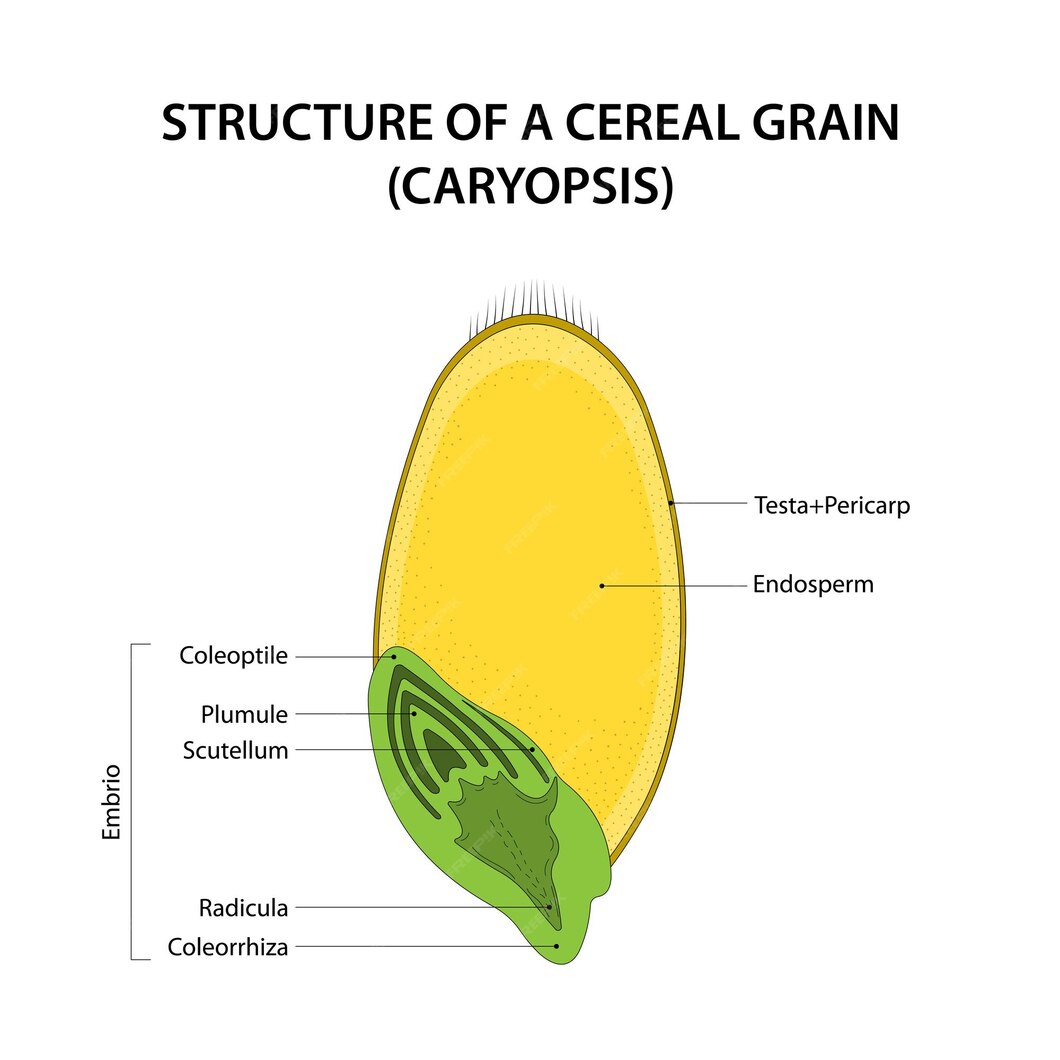

In general, it is good to know that the most “noble” part of wheat, the part used for human consumption, is the kernel or grain because it has a husk that surrounds the seed.

The grain is made up as follows:

Wild plant purpose is not to nourish us but to spread their own seeds. How do they do so freely, in an oligopoly?

When milling was exclusively done in stone mills, the resulting flour mass was exclusively wholemeal. This means that the entire grain, including the endosperm, germ, and bran, was entirely incorporated into the final product. The sifting process was typically carried out by hand and served to “clean” the flour from the bran. The more it was sifted, the whiter the flour obtained. The color of the sifted flour was crucial; white flour, in fact, produced bakery products that were whiter and perceived as more “refined” in taste. White flours and white baked goods had a higher market value and were a privilege of the wealthier classes.

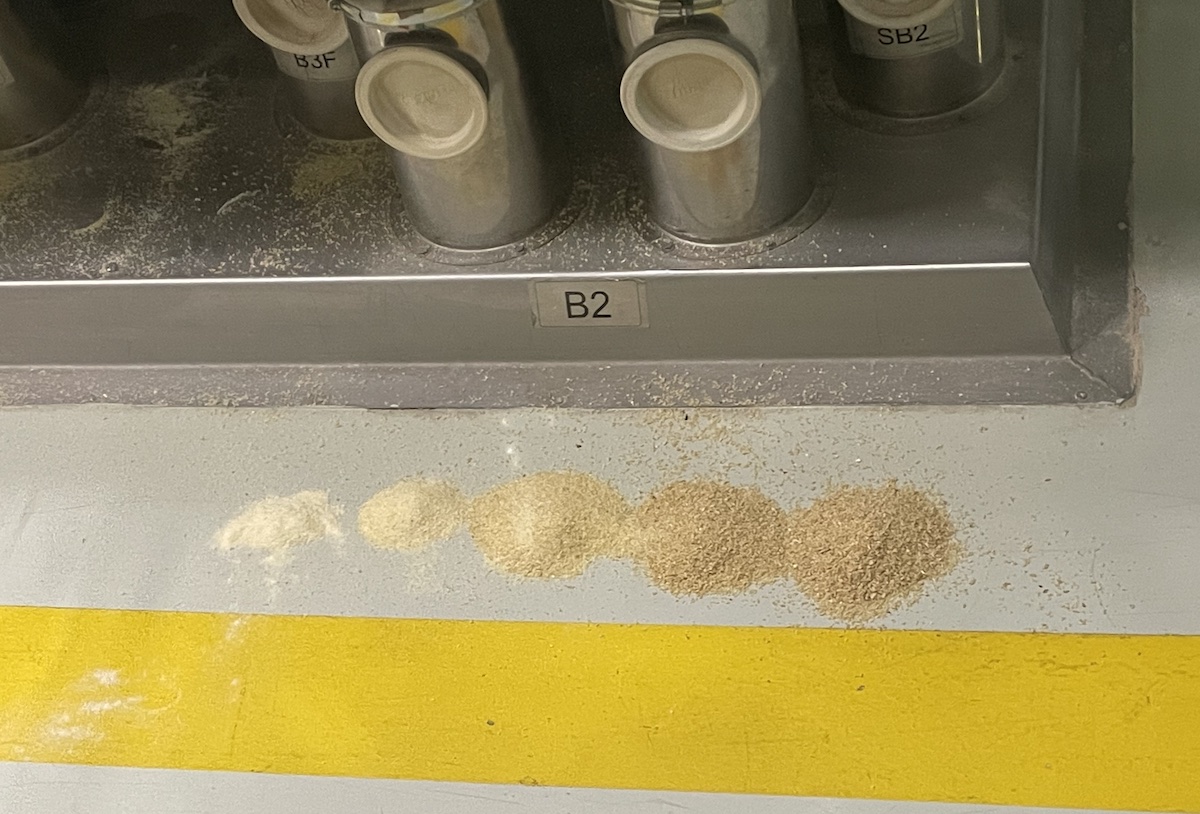

At the beginning of the Twentieth century, the food industry sought a way to optimize the process of “purifying” flour. This led to the creation of roller mills and mechanical sifters, which became widespread in Italy in the 1960s. Toward the end of that decade, the widespread consumption of “refined” flours led to the enactment of Law No. 580/67. In 1967, the official categories of soft wheat flours (00, 0, 1, 2) and durum wheat flours (semolina, semolato, wholemeal semolina) were established.

The types of flour or semolina available in the market are:

And for durum wheat:

Law No. 580/67, later amended by DPR No. 187/2001, establishes the classification of flours and semolinas, setting certain parameters, such as the ash content of the flour. The name comes from the analysis conducted to determine the mineral substance content in the flour, found in the peripheral layers of the grain: the quantity of ash allows deducing the amount of bran in the flour. The percentage determines the “purity” of the flour, the level of “cleanliness” from bran and bran particles. The more refined, “cleaner” flour is type 00, while the least refined is wholemeal.

Italian law allows labeling a product as “wholemeal” if it contains a specific quantity of fibers, regardless of the type of flour used to make it. With the circular of the Ministry of Productive Activities dated 10/11/2003 No. 168, it was established that a product can be defined as “wholemeal” even if it does not have the entirety of the grain, even if prepared with type 00 flour to which bran is added later. Products made in this way, however, are significantly poorer nutritionally, as they lack the nutritional elements of the germ and the aleuronic layer eliminated during milling.

Therefore, they are entirely devoid of antioxidants, vitamins, and Omega-3 fatty acids, which have beneficial effects on our bodies, and instead, they have a higher sugar content and a higher glycemic index. This operation benefits large companies and industrial groups, which now label products as “wholemeal” to describe something that is not truly wholemeal. Market demands: an investigation by Il Salvagente last June revealed that out of 82 analyzed and sold whole products in Italy, most are made with reconstructed flours.

The technology of roller mills – not all, as some smaller artisanal ones retain the germ – is able to exclude the wheat germ and bran, thus providing the market with significant quantities of “refined” and white flours, meeting the demand for a visually pure product with technical characteristics that make the flour and semolina more easily transformable.

Generally, before beginning the process of removing the bran and germ, the so-called “stripping of the outer coverings”, the wheat is cleaned and brushed, then soaked to soften the bran for better removal. Subsequently, the seed passes through a first set of rollers, which, by turning, free it from the bran, removing the germ, often resold at a high price to pharmaceutical companies. At this point, only the endosperm remains, the calorie and protein reserve of the seed, the “fuel”, or carbohydrates that break down into glucose molecules, one of the main sources of energy for the body, but lacking the antioxidants present in the germ and especially lacking the bran and bran particles (the innermost layer of the bran). The product resulting from these processes is a nutritionally poor food, a fast sugar.

In addition to this loss of nutritional quality in the food we eat, there is also a loss of seed biodiversity in the field because research aimed at industrial production has selected cultivars that can provide higher yields, high protein values, and technical characteristics to satisfy the food industry that processes and transforms these flours.

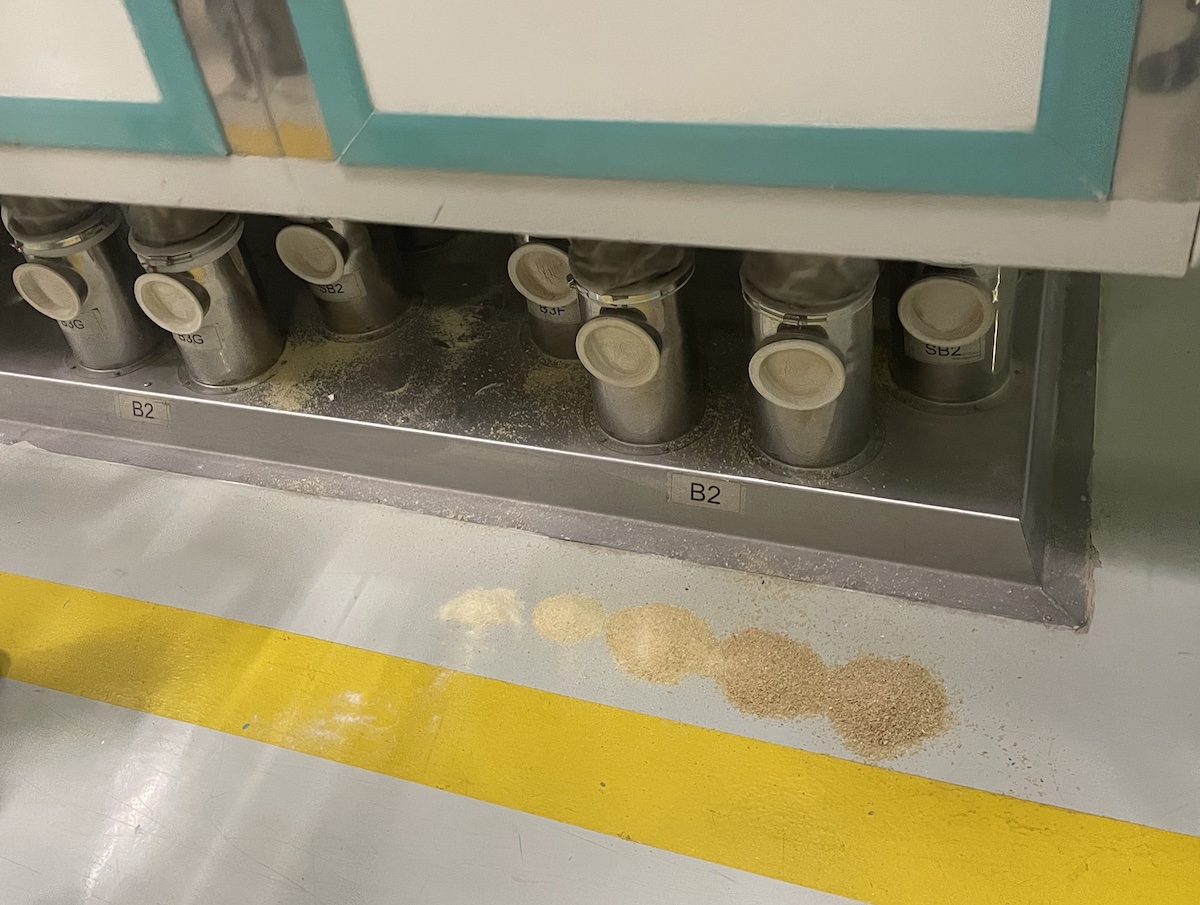

To understand how an industrial mill works and comprehend how the flour and semolina we eat are increasingly standardized and adapted to the needs of the industry, we visited the Candeal industrial mill in Melfi, in the province of Potenza, one of the largest and most modern mills in Europe, fully automated, with a production of about 800 tons of semolina per day. A mill that only grinds durum wheat, sourced from Italy, mainly from the Tavoliere delle Puglie, and from abroad, including Canada, the United States, Kazakhstan, France, Russia, Greece, and other countries. The semolina produced here goes to major Italian pasta factories, from Barilla to Divella, from Rummo to Colussi, from Pallante to Granoro, from Garofalo to Liguori.

Da oggi puoi segnalare a Slow News informazioni e documenti riservati, in forma totalmente anonima.

We tried to contact the other world leader in the purchase, processing and marketing of wheat, the Casillo Group, the largest global importer of durum wheat, owner of seven milling plants, three port terminals in Salerno, Monfalcone and Bari and numerous storage warehouses.

They never responded to our requests.

As we saw in the previous chapter, durum or soft wheat, once harvested, is transported with huge ships from one part of the world to another. Once it arrives in the port of Ravenna, or in other ports such as Bari, it is transported to the mills on board trucks and, to a lesser extent, trains. In the case of durum wheat, necessary for the production of pasta, there is a starting point: without durum wheat imports, Italian pasta simply would not exist. In 2022, the top importing countries were Canada, France, Greece, Australia and the United States.

The ancient shared history of wheat and humanity, which began with the domestication of wild cereals by humans, continues today where it all began 11,000 years ago: in Mesopotamia. It may seem like a coincidence, but perhaps it isn’t.

Enzo Martinelli, the head of Candeal, is also the president of the durum wheat mills section of Italmopa, the Industrial Millers Association of Italy.

“We produce approximately four million tons of wheat per year against a demand of about six million. Two million tons need to be imported from abroad. However, I want to emphasize one thing: the origin of the wheat is never synonymous with quality. This year, for example, Italian wheat is of poor quality due to climatic conditions, while that from Canada or Arizona is of excellent quality. At the moment, we are trying to improve the quality of Italian wheat by importing better quality from abroad to blend it together. To do this, we search for the best grains globally to obtain the semolina that our pasta factory customers request through their purchase specifications”.

Pietro Spagnoletti, head of the technical-economic area of Coldiretti Puglia, has a different opinion. According to Spagnoletti, the quality argument is an excuse to import foreign wheat: “The demand for 100% Made in Italy wheat clashes with years of neglect and unfair competition from imports from abroad, especially from areas of the planet that do not adhere to the same food and environmental safety rules in force in Italy. Farmers, for a fair remuneration of their work, are ready to increase the production of durum wheat where the use of glyphosate in pre-harvest is prohibited. Farmers are perfectly capable of producing wheat with the required specifications for pasta production, provided that processors make clear and remunerative upstream supply chain agreements”.

The main element that today certifies the quality of wheat is protein, connected to gluten which gives strength to wheat. This parameter is strongly requested by the processing industry, or rather by pasta companies, because it determines greater elasticity and toughness of the dough. Having high levels of proteins and gluten help the industry in the manufacturing process and guarantee greater stability during cooking of the pasta. In addition to the high level of proteins, some of the characteristics requested by the industry are the yellowness index (or rather, how yellow or white the pasta is), the specific weight (how much semolina is extracted from the grain) or the ash index.

Flour ashes are nothing more than the residue of an analysis in which a ground sample of flour or semolina is incinerated in a muffle (small furnace for experiments that reaches high temperatures). Depending on the technology or sample, ashing temperatures can be 550°C or 900°C. Only the mineral substances remain in the flour sample, in the form of ash. Since they are mainly contained in the bran layers, their weight percentage on the incinerated sample determines the “purity” of the flour, the level of “cleanliness” from the bran and middlings.

If flours or semolinas have such a high protein content, it is due to the pasta industry, which has urged mills and raw material purchasers to seek wheat with these characteristics. However, to have these traits, the wheat and the varieties of seeds used in the field must be developed with such genetic characteristics.

The owner of Candeal himself confirms the mechanism: “Genetic improvement [by seed companies] has developed varieties of grains, also called cultivars, in that direction. Then, of course, it depends on how it is cultivated, how it is fertilized, but the starting variety is important, and we ask [producers] for a specific variety in the field”.

Considering that it took 12,000 years for natural selection and mass selection by farmers (the so-called “ancient” or more precisely, “traditional” varieties) and only 100 years to obtain “modern” varieties, it is necessary to reflect on a few points.

The goal of genetic improvement, as we have seen in The Seeds chapter, has been, among other things, to increase yields and productivity, but also the protein and gluten index at the expense of fiber, to meet the needs of the pasta industry. The industry seeks strong wheat, produced industrially in countries like Canada, the United States, or Australia, with a particularly high protein index, a characteristic favored by industrial pasta factories and bakeries. But what happens in the human body, accustomed for thousands of years to consuming a certain type of whole grain flour, when products made from refined flours or semolinas extracted with roller mills are consumed daily and in large quantities?

According to the American writer and journalist Michael Pollan, the invention of the roller mill and the refining of flours mark the historical moment when technological evolution began to worsen food rather than improve it.

In the book In Defense of Food Pollan writes that “the gradual mechanization of production processes and continuous technological development have imposed a kind of homogenization of the food diet, which has not only affected the industrialized world but has also extended to countries in the global South”.

Today, flour has increasingly become a global commodity subject to refining and preservation processes. It is an anonymous mass-produced product, a source of sugars, economical and filling, but devoid of nutrition and stripped of its taste and genetic, anthropological, and cultural characteristics that have differentiated one bread from another over millennia. In essence, wheat has effectively become an agri-food commodity, where ties to the territory and the cultures that express it no longer matter. The producer is little more than a worker on a production line, a global factory whose planning is entirely foreign to him but from which he will be destined to depend. To cultivate those varieties of wheat in monoculture, he will need high quantities of chemical inputs and synthetic fertilizers, with the side effects already evident on the environment, climate, and health.

But there’s another detail, unknown to most, in this process of industrialization and standardization of flours: to improve the properties of soft wheat flours, various strategies are employed, including the use of technological additives that “adjust” the flours. The law does not require the disclosure of these additives on the label. This happens mainly in large mills where soft wheat is ground. Stefano Mangini, a miller with experience in many industrial mills in Spain and Italy, confirms this: “Additives are used only in soft wheat mills”, he explains. “In the United States, it’s even worse: there, it’s mandatory to standardize the product”.

In Italy, a group of researchers from the Institute of Food Sciences of the National Research Council (CNR) in Avellino has analyzed “bread improvers”, preparations often added to doughs in variable quantities between 1 and 2%, which consumers do not find in the bread ingredient list. Their function is to increase leavening, slow down the bread’s firming, and compensate for the defects of less excellent quality flours. Their research, published in the international journal Food Research International, was the first ever conducted to clarify the origin of enzymes present in improvers. In an article on Il Fatto Alimentare in 2017, researcher Gianluca Picariello explains: “Nowadays, both enzymatic and non-enzymatic improvers are used for the preparation of the vast majority of bread and baked goods on the market. The use of these formulations results in bakery products with ‘standardized,’ but ‘artificial,’ ‘homogenized,’ and less distinctive sensory characteristics from one baker to another, negatively impacting the diversification of products on the market. The use of improvers is a clear expression of how subtle the boundary is between the drive for innovation arising from numerous needs and the desire to perpetuate flavors and traditions that manifests itself with particular intensity in the agri-food sector”.

At the foundation of bread, pasta, cookies, and other baked goods introduced to the market by the food industry, there is, therefore, extensive use of refined flours, poorer in nutrients and often mixed with chemical improvers to enhance the dough’s “performance”. To achieve these flours, the genetic selection of “high-performing” grains, both in terms of field production (yield per hectare) and high protein values (better transformation performance), has been carried out to meet the demand of the pasta industry and more. Thanks to these technological characteristics, even the giants of the food industry, such as Cargill and other multinational corporations, have been able to transport and store flour in large quantities, completely separating the place of food production from the place of consumption. Without the germ, in fact, the flour is not alive. And it can be preserved for a longer time.

From the industrial mill Candeal, where the semolina used to make the pasta we eat every day and that characterizes the famous “Made in Italy” comes, we move to another mill at the Floriddia farm in Peccioli, in the province of Pisa. Gentle hills, covered with woods and cultivated fields, provide the backdrop for a family-run business that organically cultivates cereals and legumes without the use of herbicides, drying agents, and fungicides.

We ask the founder, Rosario Floriddia, why these grains are good for health and the environment. He responds as follows: “These grains are beneficial in two ways. They are more digestible and have greater nutrition because we grind the whole grain with the germ, minerals, and antioxidants. So, we are preventive for health because eating these cereals lowers health costs. The other reason they are good is how they are cultivated. They don’t need fertilizers, herbicides, or other chemical synthesis products. We rotate the fields, so one year we sow cereals and for two years legumes to give the soil time to regenerate. Plus, we have in the field more than two thousand traditional and modern varieties of seeds, so we promote biodiversity”, he explains with eyes brimming with pride.

The visit ends inside the mill. The air is impregnated with a fragrant aroma of living matter which recalls that of sourdough. “Here we process a semolina that changes depending on the grain harvested. It is never the same because we start from a non-standardized grain” explains Floriddia.

“This means being artisans. The industry that sells “Made in Italy” needs standardized grains because they have to withstand high temperatures and processing speeds, the so-called performance, but here we have chosen another path”.

This work was conceived and created by Sara Manisera, Bertha Foundation Fellow 2023, with the support of Bertha Foundation, and produced by Slow News.

Video operator: Giuseppe Pellegrino

Photo: Sara Manisera

With the collaboration of: Andrea Carcuro (Scomodo)

Illustrations: Vito Manolo Roma

Un podcast settimanale per approfondire una cosa alla volta, con il tempo che ci vuole e senza data di scadenza.

È dedicata all’ADHD e alle neurodivergenze. Nasce dall’esperienza personale di Anna Castiglioni, esce ogni venerdì e ci trovi articoli, studi, approfondimenti, consigli pratici di esperte e esperti.

La cura Alberto Puliafito, è dedicata al giornalismo e alla comunicazione, esce ogni sabato e ci trovi analisi dei media, bandi, premi, formazione, corsi, offerte di lavoro selezionate, risorse e tanti strumenti.

La newsletter della domenica di Slow News. Contiene consigli di lettura, visione e ascolto che parlano dell’attualità ma che durano nel tempo.